საერთო ცხელი ხაზი +995 577 07 05 63

Author: Tea Kamushadze

Introduction

The covid-19 pandemic, being a global incident, touched practically every sphere of life, and we must say it made us see the problems and challenges modern Georgian society faces even better than before. One of the most important things the pandemic introduced us to, next to the virus, was interacting with state institutions and the impressions from it. The pandemic showed the government’s substantial role in crises and its weak and flawed sides. The government was taking important decisions in the country and executing them (Lehtinen M & Brunila T 2021). When managing the pandemic, the state became more real, concrete and tangible (Nyers 2006). Exactly in this situation, we saw the problem there was with perceptions of the state, especially from the side of particular groups. The experience was more intensely felt among those citizens who had rarely or never experienced such a thing. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, different groups started interpreting the state differently, and it became a confrontational topic. In the meantime, the independent Georgian state had not managed to convince its citizens of possibilities that lie within equality and equal rights (Zviadadze, Jishkariani 2018). We saw the utmost acuteness of the topic of equality when managing the pandemic, as the two regions populated by ethnic minorities, Marneuli and Bolnisi, were locked down. Ensuring equality, finding ways to communicate with its own citizens and avoiding the spread of the virus happened to be self-lustrating acts for the Georgian state in the Covid-reality. The reality, which happened to be bigger than managing the pandemic, makes us think how difficult and long has the ethnic minority integration journey been in Georgian society, how weak the state is and, in many cases, how incapable it is of ensuring the protection of its own citizens. Getting to know our Covid-19 quarantine spaces will help us understand the peculiarities of that very society that was marked as alien, together with the virus.

We will try to distinguish the state’s role during the pandemic and how specific decisions or actions were perceived by the Azerbaijani community. To do so, I will summon examples from events unfolding specifically in Marneuli. It is interesting to observe how the state showed itself during the crises, what people expected from it, and what they got. What did Georgian society demonstrate when it realised the threats coming from the virus, and how did we resolve the challenges the pandemic returned to our agenda again and more acutely? In this article, I will try to conceptualise a place, a territory. What distinguishes it from other regions or countrywide? Why was Marneuli locked down at the beginning of the pandemic (23/3/2020)? First, we should understand the perception of Marneuli, of this place, in the Georgian, Armenian and Azerbaijani societies. How are the perceptions of oneself and “otherness” formed by it? Consequently, we will unpack the logic that led the state to the decision to lock down this municipality. Was it necessary, inevitable and natural for the state to establish Marneuli and Bolnisi as quarantine zones? It is also interesting whether it is possible to conceptualise this moment as a “state of war” when, during the pandemic, showing the power becomes a matter of political ontology. How the state tries to use the war effect for managing anxiety. The common feeling of insecurity and anxiety takes the form of fear and is easier to be controlled and managed. Lehtinen and Brunila, in their joint article on the political ontology of the pandemic, try to show how the use of the war ontology by the state leads us to expressions of racism when, next to the virus, representatives of other nations and different minorities are portrayed as “enemies”, and as “threats” (Lehtinen M & Brunila T 2021).

In this article, I will also review society's reaction towards the state's radical measures, a lockdown and imposition of restrictions. What forms of protest did the society choose to express their discontent? How organised was the protest, and what concrete results did it achieve? In this article, I will also discuss how the population adapted to coexist with the pandemic and state regulations. I will also touch on one of the most important traditional elements in the Azerbaijani community, the wedding, which was strongly restricted due to the pandemic. “Underground” celebration of weddings, since a specific stage of the pandemic, can be understood as an answer or reaction to state sanctions, next to other forms of protest. In the concluding section of this article, we will synthesise the experience received from the emergence of a state and the virus in Marneuli and the experience brought by their interaction. We will also discuss the process of Azerbaijani community integration into Georgian society as part of the pandemic reality.

Research Methodology

The research methodology encompasses ethnographic research and the review of existing scientific and periodic publications. Specifically for this research, I conducted eight in-depth interviews with the people who had to be “mediators” between the state and the population during the pandemic and had to participate in dealing with such matters that the state and citizens couldn’t have handled alone. During the pandemic, my respondents were vocal about the problems of Marneuli dwellers, and this way we can say they were balancing out the damage inflicted on the local community and Georgian society caused by broken communication, next to other reasons. From these people, we learned about the sufferings and experiences that the Covid-regulations caused in the minority-populated region. My respondents are both the protagonists of the pandemic stories and the heroes who are writing the history of contemporary Georgia with us. I must mention that every interview is recorded in the Georgian language. 6 of the 8 narrators are Azerbaijani, who learned the Georgian language only after their childhood. The rest of the two respondents, ethnic Georgian and Armenian respondents who live in Marneuli, represent groups of minorities in this region. Only two out of the 6 Azerbaijani narrators don’t live in Marneuli. Nonetheless, they are closely connected to it due to their own activism. Here, I must also mention it is true that I started this research after the pandemic was over, but I have been collaborating with the Azerbaijani community living in Georgia for more than ten years throughout my professional and daily work life, and I am closely observing the painful and difficult process of integration. Besides teaching the Georgian language to the Azerbaijani and Armenian citizens of Georgia, for years, I was involved in administering the Georgian language program “1+4” at TSU, including during the pandemic. Therefore, the research represented in this article is based on my personal reflections too. We can say I am the ninth narrator of these pandemic stories. My respondents' maximum openness and honesty is also conditioned by the fact that I have known half of them for many years. I considered many factors when selecting my narrators. Besides the fact that they had to be directly connected to Marneuli, I had to consider the diversity of experiences to portray events from a wider perspective. One of the narrators used to work at the local self-government, at Marneuli city hall, during the pandemic. Hence, he was the conduit and representative of state policies for the population. Considering this fact, his name will be changed when quoting him. Because of their consent, other narrators will all be mentioned with their names, despite the sensitivity of the topic.

Besides the ethnographic research, which entailed going to the centre of Marneuli and its villages, I interviewed 30 residents of Marneuli using a bilingual questionnaire. I tried to understand their experience of the pandemic and of the Marenuli lockdown using an open and anonymous questionnaire. With this research, I tried to “test” the relevance of the narratives and dispositions expressed by my narrators in their conversations.

As for the theoretical framework, the given situation falls perfectly under the understanding of legibility offered by James C. Scott in reference to the interactions between the state and local communities. We can translate this term into Georgian as discernable/readable because something is so clear that it is possible to read/interpret it. Legibility, the possibility to read, is an important prerequisite for the state systems to impose control, manipulate and exploit. When a state fails to manage some territories well, when it doesn’t understand the local population and the local peculiarities of people but continues its attempts, one of the consequences may be increasing legibility. Using different examples, James C. Scott talks about the failure of state institutions, the institutions carrying highly modern ideologies, to subjugate vast territories and control them in the name of technological progress or some other necessities (in this case, the pandemic). James C. Scott talks about the combination of four factors when the high technologies (during the pandemic, we faced, exactly, the necessity of using technologies, and their execution was in the hands of the very state) are confronted by local knowledges and by experience that he refers to by the word borrowed from the old Greek mythology, Metis. The term Metis, used by Scott, refers to the local knowledge which is underpinned by empirical evidence, is complex, and entails the unique embodiment of coexistence with the local ecosystem, it is wise and cunning at the same time (Scott 2020). In the case of the pandemic, the state locked down those territories that were less legible to it. Subsequently, in this, we can read its attempt to make them more legible/predictable through control. During the pandemic, the state was positioned as an administrator that controls society and nature, that it is self-assured, and its basis is the ethos of technological progress and physical power, legally speaking. It chooses a relatively “weak” civil society, where its control is relatively less spread. This is how we shall see the 2020 pandemic in the Georgian language when the state met its citizens in Marneuli and Bolnisi.

The first Covid-infected persons and the state decisions

Just like in the rest of the world, the emergence of the new virus Covid-19 was followed by huge resistance and diverse interpretations. Expectations about the spread of the virus strengthened from mid-February 2020. Observing the dynamic of the virus spread, it was logical to assume that it would appear in Georgia too. Public discussions about remote learning capacities and taking other preventive measures for curbing the spread of the virus indicated this. There was information spread about the lockdown in Wuhan (Radio Liberty 2020). The situation in Europe, specifically Italy, was dramatically portrayed in the media (Kunchulia 2020; Matitaishvili 2020). The appearance of the virus in Georgia was becoming more and more real with the growth of the geography of the virus. But the major question posed at that time sounded as follows – when, from where and who will be the first?

Identification of the first Covid-infected citizen marked the beginning of the new pandemic reality. Identifying the first Covid-infected citizen went beyond the medical interest and became the reason for the never-ending wide public discussions. The first information about a Covid-patient was spread on the 26th of February in Georgia. The Minister of Health Affairs made an emergency announcement on this matter and provided information on expected risks to the country’s population (Radio Liberty 2020). It was exactly at this briefing, we can say, that a new reality started that was alien to everyone, was hard to digest and turned out to be dramatic. With the discovery of the first patient, new tendencies emerged that later became state plans and policies. What did we understand, and what can be distinguished from this:

The discovery of the first patient and his identification followed a certain expectation that the virus would spread specifically in the Azerbaijani community. Such development of events was culminated by the government’s decision to lock down Marneuli and Bolnisi.

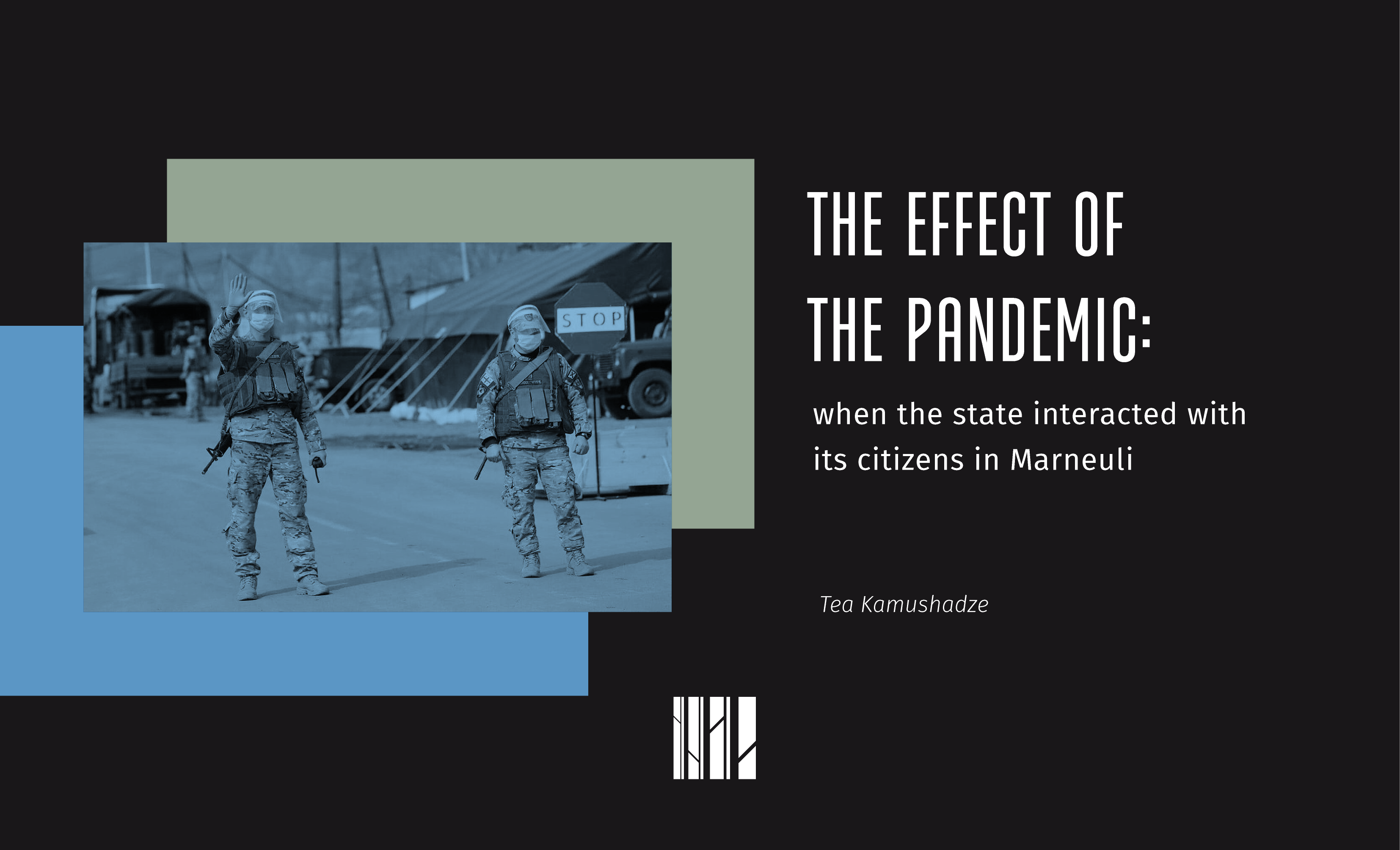

As a regular citizen, seeing military men and a checkpoint at the entrance of Marneuli was one of my intense memories during the pandemic. Identification of the pandemic with the war became part of the rhetoric of world leaders too, but the involvement of military units to control this or that territory was by itself changing the understanding of reality on a local level. Isolating specific municipalities with the help of militaries from the rest of Georgia and identifying them as a threat was, on the one hand, equating them with the virus, and on the other hand, was creating this feeling among locals that they were spared, sacrificed and punished as “others”. I think the activation of hate speech and strengthening alienation country-wide towards specific municipalities can be connected to using military units and creating the war effect.

State decision and Marneuli lockdown

We visited Camilla in Marneuli at the community radio office around two years after the pandemic was announced. Camilla is the founder of radio Marneuli and thinks she serves an important cause in terms of integrating its community and developing the country. One of the first questions I asked intended that she recall the pandemic announcement and what was happening in Marneuli then. She said that Covid was absolutely unbelievable, the virus was not taken seriously. As for the reasons, she had her opinion on why Marneuli was locked down.

“I have my understanding of why Marneuli became the epicentre of events; we were in disbelief because when something happens in Georgia, this doesn’t concern the Azerbaijani community, which means there is always something happening in Georgia, and we are distant observers. We are excluded from events, and this was the exact perception during the Covid too, that all of this is happening somewhere else, it is also happening in Georgia but doesn’t reach us. Nothing has ever reached us. The contact, the vicinity, psychologically, these don’t exist. Marneuli is excluded, is separate” (Camilla 2022).

She would recall that putting Marneuli on lockdown was followed by a certain panic and feeling of being oppressed, there was also a deficit of information, and this was creating good ground for spreading disinformation. All of this was augmented by the activation of hate speech, as described by numerous reports (TDI). Most of all, she remembered the sorrows of those people who were told to close down shops and sit at home.

“Instead of explaining, [the state] tells you, shut down the store, I will bring you bread and grain. These people were not dependent on anyone, first and foremost on the state, the state is the last hope for everyone here, and that is why they always count on the money they earn themselves. Suddenly a state tells you, ‘Close down what you created with no input of mine’” (Camilla 2022).

According to Camilla, locals have almost no connection with the state; the only connection is, is the connection established at the receipt of pension when reaching the pension age. [1]

Lack of communication was the major problem, according to her, or its mere nonexistence. She mentioned with regret that the local government was not using and cooperating with the local community radio, which broadcast in three languages. According to her, the pandemic showed that our state is very weak in integration matters, for communication is difficult with its citizens; therefore, the population doesn’t trust it.

In her April 2020 interview, Camilla explains the reasons to the anti-quarantine protests. She notes that the majority of the Marneuli population is self-employed, and their work is connected to agriculture. Therefore, quarantine measures and restrictions on movement hit them particularly hard.

“Majority have agro-loans, and all of this is made possible by loans. But it was the first time in their lives that they became dependent on the state.” (Camilla 2020).

Personally, for her, the military men and the policemen that had to control the so-called quarantine border became the symbols of the state during the pandemic. They would warn people approaching the “border” for “excessive” movements. As Camilla recalls, there were always tensions at the checkpoint. She thinks that instead of care, the state took on the control mostly.

Kamran, who works in Tbilisi at a non-governmental organisation, is particularly critical towards the roles of the state in managing the pandemic. He has significant experience and is actively protecting ethnic minority rights. Besides having work relations with Marneuli, he recalls visiting his aunt in the village of Aghmamedli in Marneuli throughout his childhood summers. In this mind, Marneuli is a special centre for ethnic Azerbaijanis. This is a place where we meet Chaikhana culture; this is a space where you hear the Azerbaijani language and see rather Azerbaijanis. According to him, it was not random that Marneuli was put on lockdown first and for the longest period of time in Georgia.

“Probably they thought in the government that they could not control the situation there, including due to the language barrier, due to the bridges being burnt. It is difficult when you don’t have the media that can relay the speech of the Minister of Health Affairs to its population in their language.” (Kamran 2022).

To explain how utilitarian government’s approach to the local municipality was, he recalled a concrete example when the Prime Minister of that time arrived at Marneuli entrance to the barricades and announced that the population of Georgia has nothing to worry about, they will surely export the agricultural products to the rest Georgia from here. As he recalls, Prime Minister said nothing about the health of the Marneuli people, about notifications for them and protecting them.

“The state won’t care about you [the citizen], your health, it cares about the products you produce, but not you.” (Kamran 2022).

According to him, when Marneuli and Bolnisi were locked down, the people thought that the virus did not exist, they were out of touch with Georgian news. They indeed watched Azerbaijani and Turkish channels, but what’s important, Georgian and Azerbaijani communities were not riding the same wave. But Kamran also remembers it well that there was Covid-scepticism in Georgian and Georgian-speaking societies, especially in the first stages.

To show the example of a punitive state instead of the caring one, Kamran recalls the request for help received from one of the Marneuli villages at his organisation. A man who did not know about the curfew went out to buy bread and got fined by the state in the amount of 3000 Lari. As Kamran recalls, this very example of battling with the state ended well because the fine was annulled. But according to his experience, there shouldn’t have been a few incidents like this in Marneuli. He said he would meet at least one or multiple people who were fined themselves or knew of others who got fined like this. Samira also recalled an incident related to fines when an old man was fined on his agricultural land for collecting grass in his own field. Davit also recalled, with a smile on his face, that a few of his colleagues also got fined in his village, Shaumiani, but no one thought of paying the fine, in the end, they did not have to pay either, said he.

The language barrier was obviously the hardest and unformidable problem that every narrator emphasises during the pandemic. Although, on certain occasions, state decisions and speeches of the high officials were getting translated, this was not enough. The situation in the Municipality would rather make you feel in an informational vacuum. The language barrier became an acute topic again, specifically in Marneuli, when people started applying for state compensation after quarantine. The state used to help those who had to stop working due to the pandemic (the Government Decree №286). To receive a one-time cash allowance for children under 18, it was also necessary to fill out the form in the Georgian language (the Government Decree №286). Due to the language barrier, this benefit was not equally accessible to every citizen of Georgia as it needed to be filled out only in the Georgian language. Kamran recalls that he and his friends from the organisation registered 500 beneficiaries in 11 days in Marneuli villages because they just couldn’t do it themselves.

Giulgun, we can say, is the only one in his village who knows Georgian fluently, and when the pandemic started, she used to study at the University then. In her letters, written from the locked down Marneuli to the magazine Indigo, we read:

“This morning, we all received an sms on the phone. The government is asking that we comply with the quarantine rules. My father called me, asking me to translate what was written there. Noone talks Georgian in the family besides me. It was also me who told the neighbours what was written there.

… In the evening, we received an sms from the government again in Azerbaijani. They sms-ed us what I had already translated for my father. Now everyone would understand.” (GiulGun 2020).

Now Giulgul humorously recalls what felt hard emotionally during the pandemic and the quarantine. She had access to Georgian information channels, also to social networks. Therefore, she felt uncomfortable being frustrated about accusations coming on social networks toward Azerbaijanis living in Georgia and towards Marneuli. She was very hurt back then, but she thinks hate speech was spread by specific interest groups, bots and trolls for specific purposes.

I have known Giulgun for years, although I first visited her in October 2022. Her village is Teqalo, 27 kilometres away from Marneuli, in the direction of Sadakhlo, you must make a turn to your right from the central road. What struck me most in the village was that yeards were in full use for vegetable greenhouses. The harvest was very impressive, which you would see in gardens from outside. Giulgun’s yard was also occupied by bean and cucumber plantations. Giulgun explained to me that there is daily hard labour in these indoor or open-air greenhouses. Every third day a car comes that collects their vegetables. This is not every day, but she always helps pick and sort the vegetables when she is at home. She, of course, spent the pandemic in the village. Neighbours would often come and ask her something, clarify some information and share their sorrows. She was also being contacted by different organisations; they would ask about the situation in the village. Once, they called her from Marneuli radio as well and asked her to organise a video survey among the villagers about their problems in the quarantine. I asked Giulgun to share the survey results with me. Something that concerned the population most of all and was much spoken about was the matter of selling their own products. The village population is mainly dependent on agricultural products, she said. Many faced economic hardship, especially because they had loaned money from the banks. So, everyone spoke of the problems related to the sale of the harvest. Giulun doesn’t remember it well if her villages would participate in protests, but she does remember protests taking place in Marneuli. Additionally, I asked her about problems during the pandemic. She gave it a thought and then answered that women were more burdened and had even more chores to do. Besides, according to her observations, violence against women also grew in some instances because men were mostly at home, getting frustrated by this and being aggressive.

Protest and manifestations in Marneuli

If there is any place where they speak of Marneuli and especially about protest, you will definitely hear the name of Samira Bayramova. Everyone knows Samira in social networks, political parties and diplomatic circles. Her active civic stance has long attracted wider society's attention. I remember her posts on the social network starting from the early period of the pandemic, not to mention that I know her personally since 2015 as an active student. As a student, I remember the first time she invited me to Novruz Bayram at her family house in Marneuli. This was a pleasant and unordinary offer from a student. Samyra is often direct and mainly critical against the government, the state, and Georgian society in general. She is relentless towards both Azerbaijani community representatives and non-governmental organisations. She says what she thinks and what she thinks is right. When the needs arise, she can also confront the representatives of radical political powers.

On January 8, 2022, when I called her cellphone and asked her for a meeting, Samyra told me, all right, but I must confirm it with security first. It had been months since she was getting police protection due to threats from the representatives of radical forces. Samyra protested the opening of the Alt-Info office in Marneuli. She painted the office windows in the colours of the Ukrainian flag, which was then followed by violent threats against her. On March 22, 2022, Samyra was recognised as a victim by the Prosecutor’s office and got her enrolled in the special protection program (Tskipurishvili 2022). Considering all this and following all rules, I met Samyra near her temporary housing in Tbilisi at a set time.

Before we started talking about Covid and Marneul, I asked Samyra – can you please explain why you are like this. She warmly smiled at me and told me she was a different child already when she was little, naughty, rebellious and disobedient. Apparently, she had been so naughty and uncontrollable that the family got scared of taking her to a public school. She used to study at a private school, which was also her advantage over her older sister. While her attempts to take advantage of Samyra were a little traumatic. Much like in the whole community, only a son was deemed desirable after having the first girl child in her family. When a girl was born again after the first child, this was not pleasant, especially for the mother of her father, who expressed her discontent to such a level that they did not give the baby a name for some time. The situation was further aggravated by doctors telling her mother she couldn’t have more children. In traditional societies, Georgian included, not having a son is taken as a big problem. I understood, but I was looking at Samyra with a big surprise, and later I asked her how she knew these things. She said the mother was telling these stories to her relatives half-jokingly but did not think the child was also hearing it, which greatly affected her. From early childhood, Samyra was close to her father and was better acquainted with his work than with the house chores of her mother. As she recalls, we may say, she was raised like a boy, which would ‘compensate’ her biological girliness. Several years later, a miracle happened, and Samyra’s mother got pregnant and was expecting a boy this time. Samyra recalls how happy this made her, she personally chose a name for the baby in the belly and said he would be called Samyr, like her. The baby was born, and the family rejoiced, but unfortunately, Samyr died soon. I was confused, asking questions like how and why?! The reason was the 90s when it was a disorder in Kvemo Kartli and the whole of Georgia. It was difficult and unsafe to visit a doctor. All in all, this was due to those conditions, the viral disease was aggravated, and the child passed away, and he couldn’t be saved. This inhibited Samyra even more and made her think of those circumstances in which some people find themselves when there is a general disorder around them. Ultimately, the son was still born and raised in Samyra’s family. Nonetheless, attitudes towards a traditional understanding of differences of sexes remained a traumatic experience for her and the whole family. So was the unsettling environment of the 90s towards minorities in Georgia.[2] Samyra told me:

„Imagine, I was the first girl from my village who came to Tbilisi and take higher education. Before, they would go for education either to Marneuli or to Baku. I was the only one integrated in Georgian society rather actively. I convinced my family that not every Georgian is a bully. This fear still exists… Well, of course, if there are students in the family who have relations with Georgians, these families are undergoing changes. They are getting convinced that Georgians are not traitors. Apparently, it is not unsafe in Tbilisi, we are a normal country, and whatever happened, it stayed in the past (Samyra 2022)”.

On the one hand, Samyra’s private, personal experience substantially explains the high level of alienation and distrust so palpable and tangible between Georgian and Azerbaijani communities. Isolation and fear of the state, which couldn’t defend us from the chaos of the 90s and spared us generations of disorder, is partly still alive in the memories of ethnic Azerbaijanis. She only manages to overcome the bad memories from the past by having relations with individual young Georgians.

According to a big part of Georgian society, Marneuli and minority-populated regions, in general, are never distinguished by their activism, they seldom or nearly never express their discontent. Traditionally every ruling party believes they will easily get majority votes in favour from the regions where ethnic minorities live tightly. Probably this was least expected, too, that Marneuli would be one of the protest centres during the pandemic. Azerbaijani community had many different protests during the pandemic. Kamran recalls two types of protests: a protest with car signals and permanent protests by farmers. Car signal protest was most significant when the state was restricting movement, and people were honking from cars parked in their yards and on the streets to let the state hear them. The deafening sound of the signals was a particular expression of the inner protest that every citizen could have had at that time due to imposed restrictions. Unfortunately, later I learned that the organisers of this protest were summoned by state security forces and given a warning. The fact that the summoned witnesses were interrogated with the sabotage charges also showed the significance and seriousness of this protest. As for the farmers’ protests, they hugely resonated and were responded both in the media and in wider society. Samyra recalls that these protests did not have organisers, and they never turned into rallies; it was just an angry and hurt population which hit the streets and protested on the one hand, the monopoly imposed by the state when it gave one specific organisation the rights to be the exclusive buyer of Marneuli agricultural produce, and on the other hand the lockdown. As Camilla recalls, besides farmers, there were common citizens who would go to the so-called border, the entrance area of Marneuli, asking to be allowed to leave Marneuli for medical purposes but were not granted these rights. Naturally, I asked one of my narrators, the City Hall employee, about this and generally about the protest. Mr Ali remembered how people would gather in front of the City Hall, but what stuck most in his memory was that the major reason for the protest was the use of hate speech against Marneuli people and that Marneuli and people from Marneuli were equated to the virus, and farmers’ activity was least memorable. According to him, protest gatherings would happen for various reasons, one being a demand to leave quarantine space. The City Hall employee recalls that for resolving these problems, they needed more effort, and they would work longer hours than usual. They were pressured and did everything to resolve concrete citizens’ problems. I can’t omit one video posted on Youtube about Marneuli City Hall titled as How Marneuli City Hall representatives are working during the new Coronavirus pandemic’. In this video, Marneuli City Hall representatives talk about how their functions grew during the pandemic and how successfully they fulfilled their responsibilities. The video shows that the City Hall representatives were also bringing pensions to the elderly, participated in the screening procedures, and what is most important they helped the population sell their agricultural products. The 6-minute video is concluded by saying how important it is to have a strong municipal government in general (Georgian Media Club 2020).

According to Samyra, people’s discontent was also caused by the feeling of people that City Hall was unfairly distributing the assistance. She has personally heard that, in some cases, assistance was distributed based on party affiliations, not on the assessment of real needs. In some of the villages, water supply was also an issue. We talked about hygiene when part of the population did not have access to drinking water, which was also causing protests and anger. Kamran recalls the time when they would travel in villages and ask the population to follow hygiene norms when one of the elderly women told them: sure, I will behave exactly as you say if you fetch me water in the village five times a day from the water spring. Therefore, there were different reasons why people were protesting in Marneuli, but one of the most important was related to providing subsistence means to them. The narrators also spoke about the company that entered the market in Marneuli, Jibe, trying to buy cheap produce. Such a low price affected villagers financially a lot and caused their discontent. When discussing this with Camilla at the office of the Radio Marneuli, one of her work colleagues recalled that their father was so angry and upset with proposed prices that he did not harvest bits from their land but ran it over with his tractor.

When talking about street protests, Camilla recalled the background situation and the phrase correctly conveying the mood of those gathered in front of the City Hall – ‘Not the virus, but starvation will kill us!’ This phrase was also used as a headline by Netgazeti, which shared the news about the gathering of the Marneuli population on March 30 (Apremashvili 2020)

When we talk about protests taking place in Marneuli during the pandemic, we can not but recall the 21st March of 2021, when the self-organised citizens purposefully celebrated Novruz Bayram in the centre of Marneuli. Setting bonfires after 9 pm, during the curfew, in the streets of Marneuli was a protest against the state, which did not treat different ethnic and religious groups equally. Sofio Zviadadze calls the 2020-21 events unfolding in Georgia when managing the pandemic, the optic illusion of tolerance. She talks about the state’s selective approach towards particular religious groups when lifting the curfew on January 6, 2021. According to her, the government did not even consider the Azerbaijani community initiative to establish Novruz as a national holiday. In addition, the community’s request to lift the curfew for one day was also ignored.

‘If not an unequal approach towards minorities and the dominant religious (Orthodox Christian) groups, this decision could be interpreted as strict adherence to regulations. But in reality, we were facing tactical discrimination. Because the government had already lifted the curfew restrictions on other occasions, including on religious celebrations, for example, when the Georgian Orthodox Church was celebrating Easter’ (Zviadadze 2021).

Naturally, the request to establish Novruz as a national holiday was also a reaction of the Azerbaijani community to the irritations and nonacceptance expressed in their direction. The anger expressed towards the Azerbaijani population and the fact of equating them to the virus significantly hindered the integration process in Georgian society. It must be mentioned that the idea of establishing Novruz as a national holiday and the request to lift the curfew for one day to celebrate it, belongs to Samyra Bayramova (Nergadze 2021). I also remember her Facebook campaign, which predicted violating the curfew. It’s worth mentioning that Samyra’s initiative widely resonated and was supported by Tbilisi activists, they travelled to Marneuli and celebrated the event together.

Celebrating Novruz Bayram is a particularly significant event for Mariam as well. She still remembers the positivity accompanying the celebration of Novruz since childhood. In her recollections, it was a real new year when they would bid a farewell to winter and celebrate summer. She said she knew the 21st of March would be good weather despite the weather days before Novruz because this was the beginning of true spring. Mariam works at the Democracy Development Center of Marneuli and lives in the village of Tamarisi with her family. Despite opportunities, she has never thought of living elsewhere. Next to it all, it is an interesting sensation to represent the majority as an ethnic minority yourself in a place where an ethnic minority group is in majority.

With her long-term experience and efforts, Mariam is actively participating in the integration of ethnic minorities. We spoke a lot at her office about the projects that they execute, especially since the pandemic. During the Covid restrictions, they actively used social networks and created an open group called “Stay at Home – Live from Marneuli” (https://www.facebook.com/groups/274468463543836). With the help of this group, they used to receive information about the needs of particular individuals or families, and they would put them in touch with the people who could solve their problems. There were informational posts published on this platform. They had municipality representatives added to this group as well. Besides managing the Facebook group, Mariam had to also work at Marneuli TV due to the fact that temporarily, during the lockdown, one of the TV hosts who lived in Teleti was restricted from movement after Marneuli was put on lockdown. When she was asked to help, Mariam agreed without hesitation. Despite the fact that she also feared the virus, she would go to work every day. She was spreading the necessary and essential information this way. Respectively, she vividly remembers Marneuli’s protest details and the attempts to resolve the issue.

I asked Mariam what her observations were about the effects of the pandemic on the integration of Marneuli society. To answer this question, she recalled the solidarity the Merneuli people expressed towards one another and their many individual initiatives. Specific individuals and stores were distributing food and necessary things for free. The only thing was that Tbilisians would bully us from outside. All in all, if not the external factors, be it Karabakh War, etc., the virus and the pandemic were our common problems, and blaming each other would help at all.

Life in the Pandemic and the adaptation period

Despite their confusion and feeling of injustice, the Marneuli population found ways to cohabitate with the pandemic; this was mainly manifested in the attempts to evade regulations and in a very high degree of solidarity.

On the central roads of Marneuli, you would notice wedding dresses displayed in shops and active beauty saloons. On the 25th of September of 2022, I walked almost the entire Marneuli to browse wedding venues, I was curious about what was going on and how they were preparing for the weddings. I was impressed with what I saw. Both the scale of the venues and the preparations I was seeing was impressing me a lot. They would also answer with enthusiasm if a passerby asked a question. People preparing the venue showed zeal to explain what and why they were doing. Sometimes they spoke in broken Georgian; sometimes, they’d call others to explain things to me in Georgian or in Russian. I visited five wedding venues that day, and all of them were actively getting ready for a wedding. I noticed cars decorated with ribbons on the streets, overcrowded saloons and supports of the brides hanging around. As Ceyhun told me, the significance of a wedding, its scale and pomposity, is particularly noticeable in Spring and Fall in Marneuli.

I wouldn’t be so interested in these topics if it weren’t for my encounter with Ceyhun a few months ago. Ceyhun works as a journalist at one of the famous private TV channels, and his popularity goes beyond Marneuli. He is one of the first people who was admitted to the Georgian language prep course and received higher education in Georiga at the first Georgian school. I have never taught Ceyhun Georgian, but I still see him as my student. When studying the preparatory course, he would visit the dean’s office several times a day and always pose some questions. Once, he told me, don’t be offended that I ask so many questions, this is my practice in the Georgian language. Who would have complained about the polite boy who always knew it well where he was headed and what he wanted?! Ceyhun took a long road until he arrived to his recognition from Georgian society. He was always careful and had a humorous attitude towards the xenophobia expressed towards the Azerbaijani community.

“I was on shoots [in Bolnisi]. I approached sitting taxi drivers and asked: the pandemic is over now, what is the situation now, how do you feel yourself? He started swearing. They brought it to us, he said… I shut up, couldn’t say anything.” (Ceyhun 2022).

Ceyhun doesn’t generalise the xenophobia of a particular person on all Georgians. He perceives himself as part of Georgian society and is always careful in his assessments. I asked him to share what he thought of Marneuli. He said, for him, Marneuli is a strong and active place economically, it is always in motion.

“Marneuli is a city of people with money, of millionaires.” (Ceyhun 2022).[3]

This half-jokingly expressed opinion was a little unexpected for me. To clarify, I asked what he meant by that. He said the Marneuli population works day and night, and Azerbaijanis who are from here are very hard-working. He believes pompous weddings, held in hundreds in the Fall, are a manifestation of this. According to him, all of this is related to finances, plus the dowry and additional expenses related to this. Wedding costs are constantly increasing, and people employed in this sphere are getting reach. Basically, he specifically distinguished the wedding business. Let’s ask ourselves what Marneuli was doing for two years. Were there no weddings? Mariam recalls sanctions and the attitudes of the population towards them and says that even though gatherings were prohibited, right after the quarantine was over, you would constantly hear wedding sounds. Mariam remembers what she overheard at a saloon: people would also come here from other regions, and the Police would pretend not to hear. Sometimes we ask ourselves, why were we even in lockdown?

I discussed this topic with Camilla, too; she also confirmed the celebration of weddings during the pandemic:

“Weddings were still held [in Marneuli], even though there were restrictions, people still organised them for 150 guests instead of 400. They still had to hide. It seemed the local self-government knew. They would ask not to post a picture, post it after five days, and this is how it was. Some posted the pictures after having a child”. (Camilla 2022)

Giulgun also remembered weddings in the village during the pandemic; some might have been fined, she said, but not that they cared. I asked why weddings are so important for people here. She answered that weddings are particularly important for women as this is the only chance to go out for many of them. This is the moment when a woman leaves the house, gets ready, communicates with others and feels like part of society.

About the weddings during the pandemic, Samyra recalls:

“When the rules were very strict, there were no wedding celebrations. But those who were close to the local self-government could still celebrate. Some of them knew they would get fined but were still celebrating: we can’t do anything, the wedding has to be celebrated in any case!” (Samyra 2022)

So, celebrating a wedding during the pandemic and participating in it turned into a form of protest and a type of adaptation for the population. One of the most important elements of this culture was turned into a specific form of resistance and disobedience. Celebrating weddings during the pandemic can be understood as a reaction to restrictions perceived as unfair and repressive.

Absolutely every narrator recalls feelings of special solidarity and specific actions accompanying this feeling during the pandemic. After Marneuli was locked down, there was information spread on social media about how bakers were distributing bread for free. Samyra herself initiated a money collection that bought the products for the neediest.

“I would say Marneuli is an exemplary city in Georgia in terms of social assistance, sharing, and support.” (Ceyhun 2022).

Social networks also shared information about a family in Marneuli village Maradisi who was transferred to hospital due to Covid but got its potato field ploughed by other people (Radio Liberty 2020). Camilla and Ceyhun remembered the Marneuli mosque’s positive role in distributing humanitarian aid. Ceyhun says even the city hall used to convey the products it purchased to the mosque, as it knew who needed assistance the most. Samyra recalled that the assistance was distributed by Imam Ali Mosque and the Marneuli Eparchy. I followed up on this with her, I assumed that the Eparchy representatives would help Georgians and the Mosque would help Muslims. Samyra said no, it would give assistance to both. Samyra remembered that when Imam Ali Mosque representatives were not given permission by the City Hall to drive around in cars, they got creative and thought of something else.

“The sheikh of the Highest Theological Division of Muslims of Georgia, Mirtag Asadov, said that Marneuli City Hall did not allow to drive around the city to distribute the products, for what reason they used a donkey to carry a cart (Radio “Marneuli” 2020).

As Mariam says, during the pandemic, no one would differentiate citizens from one another, everyone was helping each other. “Camilla’s Radio” and her whole collective were trying to reach the Armenian community in their language in Marneuli. One Armenian speaker who works on the Radio now translates the news into Armenian. Despite this, as Camilla says, the Armenian population of Marneuli is pretty lost in identity, and it is not easy to understand their needs in Marneuli.

Davit got admitted to a Georgian prep course in 2018. He was one of my distinguished and memorable students. When asked where he is from, he answers that he is from Shaumiani, not Marneuli. To him, Marneuli is rather associated with the Azerbaijani community, much like it is for most of the Georgian population. Therefore, he doesn’t identify himself with it. He tells me a story that, once, when states and borders did not exist in this form, Marneuli was just the same kind of village as Shaumiani, where his ancestors lived. When I asked where his villagers buy necessary products, he answered that Shaumiani has all sorts of stores, markets and supermarkets. He says with regret that they don’t have banks and such institutions in Shaumiani. Davit is studying computer science, and he used to know technology well before his university admission. Years ago, when teaching the Georgian language, I remember he told me he already had an independent income and was a much-needed person in the village. If anyone’s telephone or computer breaks down, they bring it to me. When I met him, I told him his profession must have been handy during quarantine. He recalled many occasions when villagers asked for advice and help. He was helping relentlessly. For me, the language situation was interesting in his village. He knows Georgian well himself. He already spoke Georgian well when he got admitted to the course. I asked him what language they speak with Azerbaijanis on the Marneuli market or in the stores. He told me he knows Azerbaijani well and can speak it as well, much like Russian. He told me with a smile on his face that he is not introverted and asocial as a programmer, and he loves to communicate a lot. As for his villagers, they know Russian and Azerbaijani better than Georgian. Like other narrators, I asked Davit how his village population saw the pandemic and lockdown. His sincere response resembled the answer of others, to the locals, the virus wasn’t real, but the lockdown and the restrictions were, and were directed against them instead of protecting them. I must say this feeling was not alien to Georgian-speaking society either. But in the case of Marneuli, perceptions were much more intense, aided by the ethnic aspect, from inside and outside. As a reaction to decisions by the state, a particular societal group created a desirable ground for conspiracy theories and disinformation and sought ways of evading sanctions.

In terms of numbers, the survey results in the Marneuli population substantially reinforce the opinions my narrators expressed above. We can distinguish one difference, though, that one-fifth of the surveyed believed that putting Marneuli on lockdown was justified and necessary from the side of the government. Besides, they said that the government did the maximum at its disposal for the safety of the population. A positive assessment of the state management of the pandemic is different from the disposition of the Marneuli population as described by my narrators, but in a way, it is balancing it out. Online respondents expressed interesting ideas about how they perceive Marneuli’s territory. If, for my narrators, Marneuli is associated mostly with the Azerbaijani community, part of the narrators also speaks of it as a multicultural, diverse place.[4] Therefore, the remote and anonymous survey is nailing and coinciding with the facts retold by the narrators.

My narrators, with whom I had candid and long conversations on any pressing issue that surfaced by Covid-pandemic and the Marneuli lockdown, told me that criticism of state policies is not related to Georgian society. Their majority especially noted that they felt particular support and solidarity from the active part of Georgian society during the lockdown in Marneuli. Most of them are critical of the Georgian state that couldn’t provide adequate care for ethnic minorities, their integration and protection. They would also spread their criticisms to neighbouring countries that try to have influence and strengthen it in this region, which, in their opinion, can also hurt the integration process. The experience of a pandemic that was specific to them got linked to active communication with the state and united diverse but straightforward opinions. Their criticism shows the gaps in the integration policies of the state more vividly. Despite that state used military and war effects to manage the pandemic, hereinafter activating hate speech and causing alienation, the criticism is less directed at ethnic Georgian citizens. They think the pandemic was a big challenge to every Georgia citizen, bringing existing problems to the surface. The pandemic also showed that existing problems needed recognition and resolution, not hiding.

Conclusion

To conclude, the pandemic returned unresolved issues to the agenda. Perceptions of the state were surely problematic among ethnic minorities. The use of war effects by the state and bringing the militaries to the entrance of Marneuli and Bolnisi itself facilitated the growth of dissatisfaction with minorities living there. The pandemic made the state more concrete and tangible for its citizens, which was a novelty. Unfortunately, this connection with state institutions did not create a positive experience, which on the one hand, was related to restrictions imposed and excessive mobilisation of a repressive apparatus during the pandemic and, on the other hand, to the unpleasant memories of the 90s. The collapse of the Soviet Union and subsequent events that unfolded in Georgia has particularly scarred the relationship between Georgian and Azerbaijani communities. In the case of Kvemo Kartli, we had an alienation that was not targeted by sufficient efforts from the state to overcome it. During the pandemic, against the backdrop of informational scarcity and uncertainty, the local community took the state’s decision to lock down Marneuli and Bolnisi as actions directed against them. Restrictions imposed by the state violated a routine of traditional life, mobility and various economic activities.

From today’s perspective, it is difficult and impossible to decisively assess the necessity of the lockdown of Marneuli and Bolnisi. It is a fact that the state did not have direct channels of communication with the population of these municipalities. Therefore, it chose a relatively easy way – of imposing control and lockdown. Although, even in the conditions of a lockdown, communication with locals proved to be essential. We can say that the reality around the pandemic showed insufficient efforts taken by the state and weak integration policies. The pandemic also showed that next to adaptation, the Azerbaijani community can organise a protest, can find ways to express it, and, when necessary, it can show its solidarity. Solidarity, next to traditional ways of being, became the means to deal with the pandemic. The inconsistent and unfair approach of the state was confronted by the solidarity and creativity of the local population, which is called Metis by James C. Scott. The local community responded with experience and knowledge to the attempts to impose absolute control by the state. Experience of the pandemic showed that the Georgian state barely understands its citizens and that it has to divert its effort from its control to facilitate their protection, integration and participation.

This article is produced under project [XXX], funded by a grant from the Institute of War and Peace Reporting (IWPR) with the support of the UK Government. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author[s] and do not necessarily reflect those of IWPR or the UK Government.

![]()

Bibliography

Club, G. M. (August 1, 2020). How did Marneuli City Hall representatives work during the Covid-pandemic. Retrieved from Time for Self-Government:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=78ySwV75coA

Lehtinen M and Brunila T (2021) A Political Ontology of the Pandemic: Sovereign Power and the

Management of Affects through the Political Ontology of War. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:674076. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.674076

Nyer, P. (2006). The Accidental Citizen: Acts of Sovereignty and (un) Making Citizenship. Economy and Society 35 (1), 22-41.

Scott, J. C. (2020). Seeing like a state. Yale University Press.

Ambebi, A. (May 1, 2020). Women in Marneuli ploughed the land of a Covid-infected family. Radio Liberty.

Ambebi, A. (26 February 2020). First Covid-infection case recorded in Georgia. Radio Liberty.

Ambebi, A. (22 January 2020). China warns its population not to visit the city where the virus spread from. Radio Liberty.

Afrimashvili, S. (20 March 2022). "Not the virus, but hunger will kill us" - the population gathered in front of the City Hall. Netgazeti.

Boshishvili, A. (2020). Ethnic and demographic lendscape of Kvemo Kartli (history and contemporaneity). Tbilisi: TSU.

(2019). The research on the participation of ethnic minority representatives in political life. Tbilisi: Open Society Georgia Foundation.

(2021). Participation of ethnic minorities in political life remains a challenge. Tbilisi: Social Justice Center.

Kakha Gabulnia, Rusudan Amirejibi. (2021). Minorities of Georgia: removing the barriers in integration process. Tbilisi: A joint project by Levan Mikeladze Fund and the European Office of Carnegie Endowment for International Peace - Future of Georgia.

Kunchulia, L. (26 February 2020). Corona-virus: Iran and Italy conditions raise questions in Georgia. Radio Liberty.

Matitashvili, V. (24 February 2020). Situation regarding the Corona-virus - Italy, Iran, China, South Korea. Publika.

Mamedova, K. (23 April 2020). What causes anti-quarantine protests in Marneuli?

Melikishvili, L., & Janiashvili, L. (2021). The integration of ethnic groups in Kvemo Kartli (Armenia and Azerbaijan). Tbilisi: TSU.

Nino Lomadze, G. N. (2020). Letters from Marneuli Villages. Indigo.

Sophio Zviadadze, Davit Jishkariani. (2018). The problem of identity among Azerbaijanis of Kvemo Kartly. OSCE High Commissionare on Ethnic Minorities. EMC, 1-17.

Kamran Mamedli, Konstantine Chachibaia. (2021). Dmanisi Conflict - Ethnic Lines of Mundane Conflict. Tbilisi: Social Justice Center.

Tskipurishvili, N. (6 April 2022). Prosecutor's office enrolled Samyra Bayramova in a special protection program. Netgazeti.

[1] Low participatin levels and involvement in political life of ethnic minorities is evidenced by researches conducted around Georgia. Some numerous reports and recommendations speak about reasons to this, low level of knowing the state language, self-sufficient agriculture, stereotypical perceptions and Soviet legacy (The research on participation of ethnic minority representatives in political life, 2019) (Participation of ethnic minority representatives in political life remains a challenge, 2021) (Kakha Gabunia, Rusudan Amirejibi, 2021), (Melikishvili&Janiashvili, 2021).

[2] In the 90s, the collapse of the Soviet Union was followed by the reinforcement of nationalist traditions. This facilitated ethnic minority groups living in the country to become labelled as the “others”. This was augmented by two conflicts inside the country, recognised as ethnic conflicts. Therefore, the division of the country’s population based on ethnicity was not creating favourable conditions for imagining the establishment of a united independent state. For rethinking the Dmanisi Municipality conflict that happened on May 17, 2021, research authors dive into the causes of confrontation and recall 90s. As the authors say, discussions are hugely complicated by the traumatic memories of the population and the deficit of scientific reflection in Georgian academic circles (Kamran Mamedli, Konstantine Chachibaia, 2021).

[3] A particular research that speaks about the conditions hindering Azerbaijani community integration, and amongst others names social and economic deprivation (The research on the participation of ethnic minority representatives in political life. 2019)

[4] The researcher, Alexandre Boshishvili, referring to historical sources and documents, speaks of the historical experience of Kvemo Kartly and Marneuli, describing them as multiethnic and multicultural territories (Boshishvili, 2020).

The website accessibility instruction