საერთო ცხელი ხაზი +995 577 07 05 63

Contextual Overview:

More than two months have passed since the escalation of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, which forced almost the entire ethnic Armenian population to flee. Despite Baku's commitment to respecting the rights of ethnic Armenians, most have hastily fled the region, fearing violence or potential loss of their freedom to use their language and practice their religion and customs. According to various estimates, a few dozen ethnic Armenians remain in Nagorno-Karabakh, who do not want to flee for different reasons: They do not want to leave the graves of their relatives, some are still hoping to find their missing children, others have taken it upon themselves to care for their elderly parents or the stray animals left behind.

During the six-week war in 2020, Azerbaijan recaptured from Armenian forces vast areas of Nagorno-Karabakh and its neighboring territories that had been held for three decades. As a result of this war, some 37,000 people found refuge in Armenia[1], and several thousand people from the captured territories moved to the central part of Karabakh, which was still under Armenian control at the time. Over 6,000 people (from both sides) were killed in the fighting, that ended in a Russian-brokered peace agreement. Moscow sent about 2,000 peacekeepers to the region[2]. After the 2020 war, there was a faint hope in Armenian society that a peacekeeping force would provide stability for a while and allow Armenia and Karabakh to recover a little from the devastating shock of the war. However, these hopes were not fulfilled. Not only did the peacekeeping contingent do nothing to ensure the security of the Armenian population in Karabakh, but it did not even have a clear mandate to act in the region[3].

After the mass exodus of Armenians in September 2023, the streets of the regional capital, which Armenians call Stepanakert and Azerbaijanis call Khankendi, were left empty and littered with rubbish and smoking piles of burnt belongings and documents. During the exodus, Azerbaijani authorities arrested several former members of the Karabakh government and called on ethnic Azerbaijanis who fled the region during the First Karabakh War three decades ago to return. In their daily bulletin from 23 November, Russian peacekeepers report that since 19 September they have dismantled 12 permanent and 16 temporary monitoring posts in the region. As contradictory as it may sound, the Russian peacekeeping contingent continues to fulfil tasks at 18 monitoring posts, informing Baku of its activities aimed at ensuring security and respect for humanitarian law with regard to the [missing] civilian population[4].

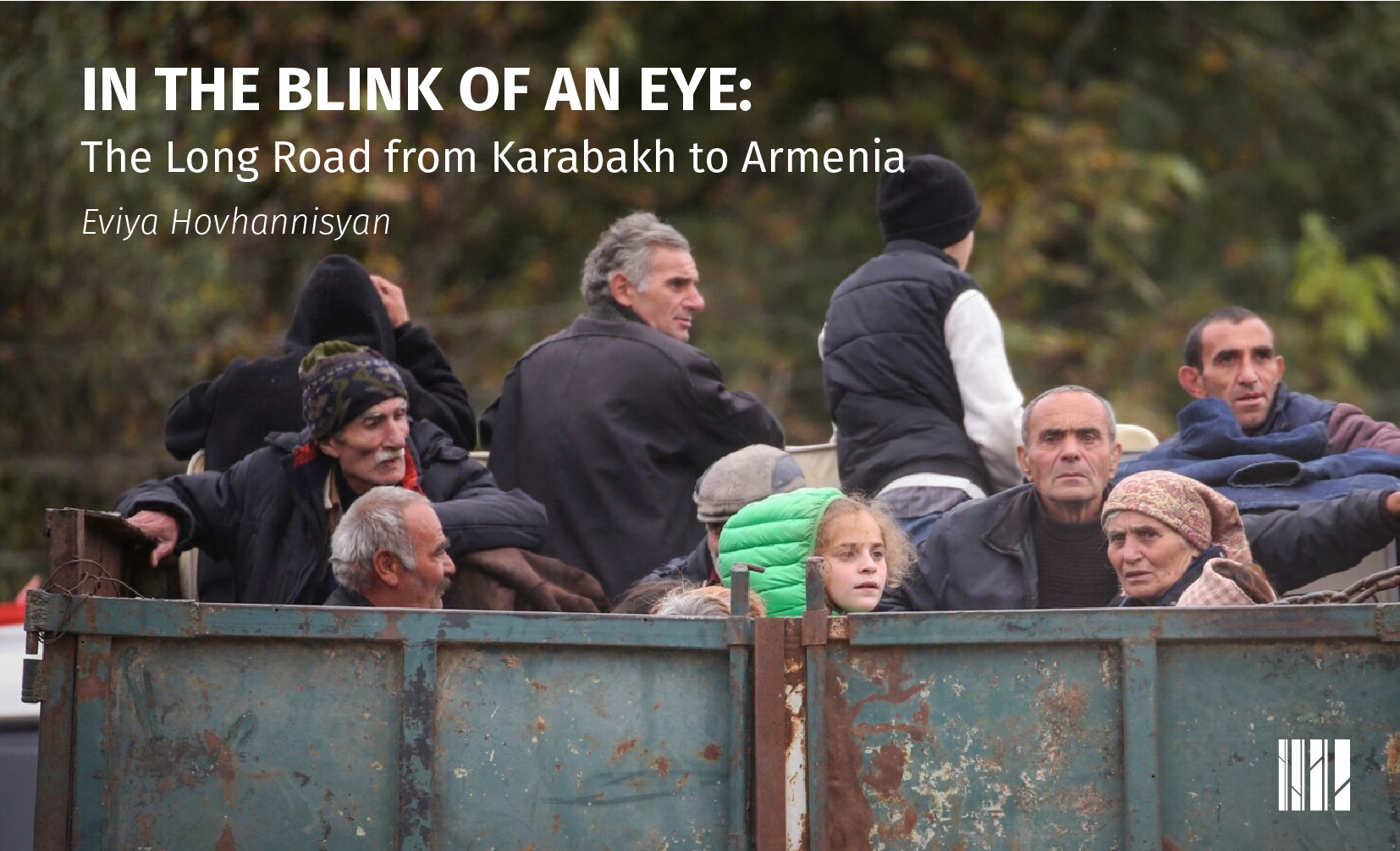

The exodus from Nagorno-Karabakh began almost immediately after Azerbaijani forces took control of the region. Within days, it was all over: Almost the entire population of the territory fled, leaving behind everything they could not carry. "A week before 19 September, we already felt that there were large movements of Azerbaijani troops in the area of Aknaghbyur and Avetaranots villages. That day was an ordinary morning, nobody thought that a battle would start, we have been used since the nineties that an attack usually happens at dawn, at 5-6 am, this time the battle started in the afternoon of 19 September, at one o'clock," - recalls Hovik, former head of Karmir village in Nagorno-Karabakh[5]. No one expected it could happen in just a few days. Hundreds of cars, with a lifetime's worth of belongings on their roofs, moved slowly along the Lachin Corridor, the only road between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia. Then buses, trucks and ambulances lined up in long queues on the mountain road. “My husband lost his leg during the First Karabakh War, in 1992,” - said Karine, a displaced woman from Martakert, - “We were afraid that once the Turkish border guards started questioning us, they would realize that Zhorik was a war veteran and wouldn’t allow him to cross the border. We thought it would be right for him to drive the car past the military outpost on the Hakari Bridge and thus go unnoticed. That’s what happened. We were told to walk, while my husband crossed the bridge by car. I covered his legs with a jacket so that they wouldn’t notice anything and ask questions. There were fears that men who had participated in the war would not be allowed out of Artakh, so we were lucky[6].” More than 60 people died during the arduous and slow journey, which took more than 40 hours. The exodus followed a nine-month blockade of the region by Azerbaijan, which left many people suffering from malnutrition, dehydration and lack of medicine.

For months, since 12 December 2022, Azerbaijan has blocked the Lachin Corridor, the only and therefore vital road connecting Armenia and Karabakh. The people of Artsakh relied on Armenia for medicine and emergency medical care, and for the transportation of basic goods and supplies, including food. The purpose of the blockade was to starve the population of Nagorno-Karabakh and put psychological pressure on them. The blockade was also timed to coincide with the middle of winter. The Azerbaijani government shut down the pipeline carrying natural gas from Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh and also disrupted the electricity grid, leaving the local population unable to heat their homes, schools and businesses, while power cuts continued to cause hardship. The main aim was ethnic cleansing by forcibly displacing local Armenians from their homes when the road was opened.

After Azerbaijan imposed a blockade on Karabakh in December 2022, the Government of Armenia formed a special working group to address the humanitarian problems of the population. It subsequently evolved into the "Humanitarian Centre", which was established near Kornidzor village at the entrance to the Lachin Corridor from the Armenian side. Following Azerbaijan's large-scale attack on 19 September, the Humanitarian Centre was tasked with managing the reception and immediate accommodation needs of the forcibly displaced[7]. Refugees[8] were then directed to Goris, the nearest Armenian town to the border with Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh, for registration. From there, within days, buses were organized to redirect refugees to cities across the country.

The material was prepared as part of a project supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) and Kvina Till Kvina, "Encouraging Conflict Transformation by Critically Rethinking Conflict-Related History and Strengthening Women's Perspectives". SIDA and Kvinna till Kvinna may disagree with the views presented here. Only the author is responsible for the content of the material.

[1] Persons in a refugee-like situation, accessed: 03.12.2023, URL: https://www.unhcr.org/am/en/persons-in-refugee-like-situation.

[2] Sargsyan L., Russian peacekeepers in Artsakh: Ambiguity of the rules of engagement, published: 19.05.2021, accessed: 25.11.2023, URL: https://evnreport.com/politics/russian-peacekeepers-in-artsakh/.

[3] Post-war Prospects for Nagorno-Karabakh, published: 09.06.2021, accessed: 03.12.2023, URL: https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/caucasus/nagorno-karabakh-conflict/264-post-war-prospects-nagorno-karabakh.

[4] Information bulletin of the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation on the activities of the Russian peacekeeping contingent in the zone of the Karabakh economic region of the Republic of Azerbaijan, published: 23.09.2023, accessed: 25.11.2023, URL: https://mil.ru/russian_peacekeeping_forces/bulletins/more.htm?id=12487279@egNews.

[5] Davtyan A., Makiyan H., "You can recreate the home-place, but you cannot recreate the homeland": the head of the village from Artsakh, Hovik Petrosyan, published: 30.11.2023, accessed: 02.12.2023 URL: https://rb.gy/6jg3b5.

[6] Interview with the displaced family from Karabakh at the Metsamor Hotel, 15.10.2023.

[7] Abrahamyan G., Services available for the forcibly displaced from Artsakh, published: 03.10.2023, accessed: 26.11.2023, URL: https://evnreport.com/new-updates/services-available-for-the-forcibly-displaced-from-artsakh/.

[8] In the text, the terms refugee and forcibly displaced person are used interchangeably and equally.

The website accessibility instruction