საერთო ცხელი ხაზი +995 577 07 05 63

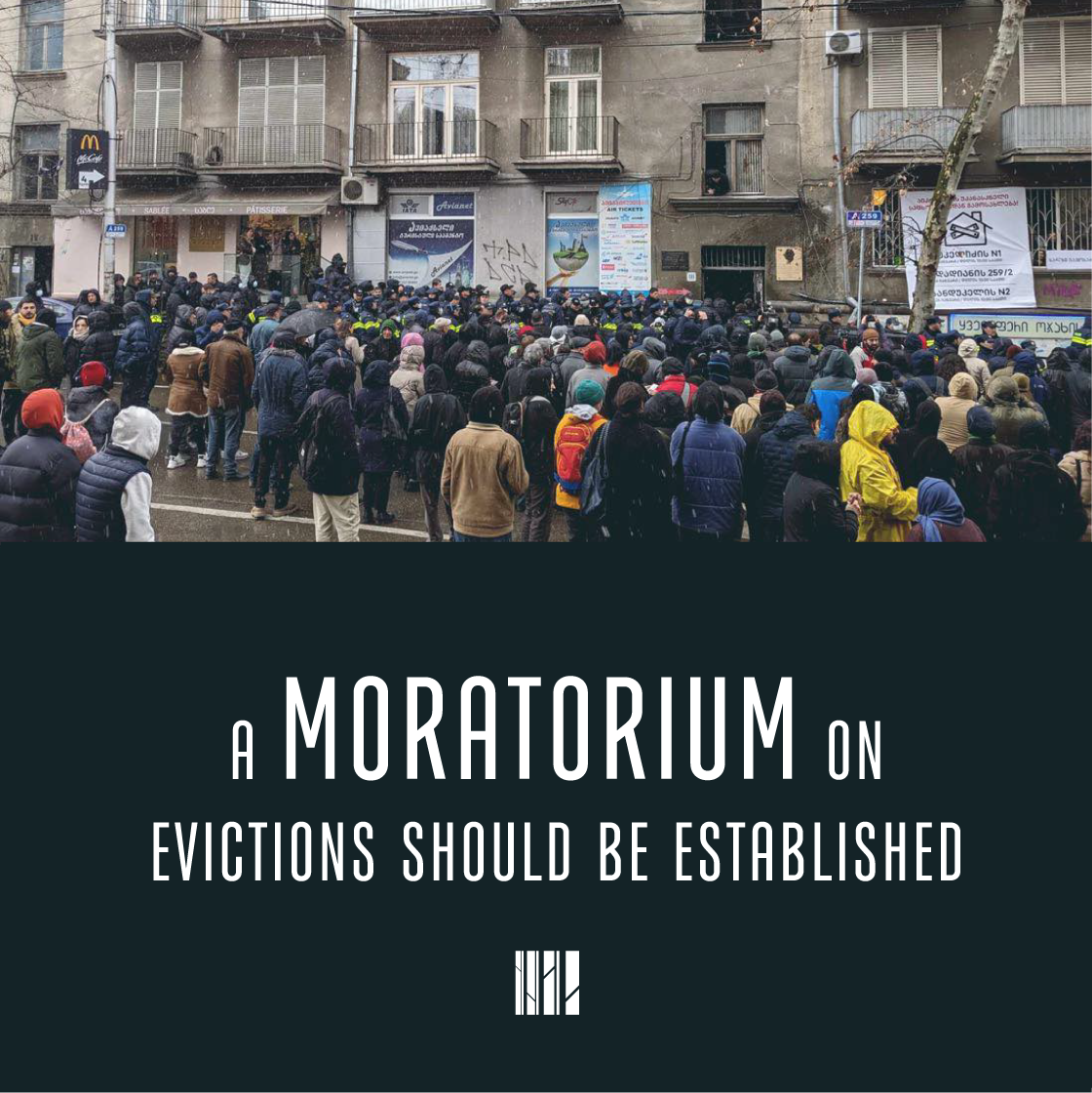

The Social Justice Center is addressing one eviction that has already been carried out, as well as two ongoing evictions this week from the sole residential properties. We urge the state to cease forced eviction and to adhere to, at the very least, the minimum standards within the existing highly flawed legislation and practice.

The eviction of a family from a residential apartment on Kekelidze Street yesterday is a clear indication of poverty, social insecurity, and long-standing systemic failures in the state's policy. The state's inadequate provision of social protection leaves the population vulnerable to moneylenders and financial institutions. When debtors are unable to repay loans due to dubious contract terms, they face eviction. In these cases, the state employs its resources and repressive apparatus to forcefully evict individuals, thereby further infringing upon their right to housing.

Forced eviction is a grave infringement upon human rights, resulting in the violation of not only adequate housing but also numerous other rights. Eviction should only be considered as a last resort after all other options have been exhausted and when suitable housing has been provided for those being evicted.

It is important to reiterate that the state's assistance to individuals before, during, and after eviction is not an act of kindness, but a legal obligation based on various international standards, particularly the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. Georgia has taken responsibility to abide by these standards since 1994.

The eviction issue is multifaceted, resulting in a range of obligations for the state. Nevertheless, in accordance with international norms, the nation is obligated to establish sufficient guarantees:

In accordance with international standards, governments are striving to undertake various measures and enact appropriate policies to prevent eviction and provide ongoing assistance and empowerment to individuals facing eviction. Each country's experience varies, but common measures include implementing responsible lending policies, offering fair loan conditions, expanding housing funds and social housing systems, providing debt restructuring assistance, offering one-time or multiple monetary aid to individuals at risk of eviction, offering consultations, facilitating mediation between parties, prohibiting evictions during winter, providing alternative housing for evicted individuals, and implementing other relevant measures.[6]

Conversely, the situation in Georgia is highly problematic. It is important to mention that in Georgia, the established maximum interest rate limit for loans is 50%.[7] The research conducted by the Social Justice Center reveals that private moneylenders play an active role in the expropriation of real estate through auctions, alongside banks and microfinance institutions. Recent research indicates that over 50% of real estate was sold through forced auctions by individual sellers and other legal entities. The economically disadvantaged segment of the population, lacking a sufficient financial track record and resources, faces restricted access to bank credit and therefore resorts to borrowing from private individuals under even more burdensome conditions.

In 2018, the state implemented regulations that imposed restrictions on private individuals' ability to lend money. One of the prohibitions was the signing of a mortgage agreement between private individuals unless the lending entity had more than 20 persons with a loan or credit obligation at the same time. This means that securing a loan with real estate was not allowed, except in the case of "lodging with a loan". This regulation aimed to restrict the discretionary power of private lenders, specifically in relation to the terms and conditions of the contract, in order to prevent unfair practices and manipulation. Contrary to expectations, the actual outcome was the opposite, leading to a clandestine movement of private philanthropy, resulting in deteriorating circumstances for borrowers.

According to information gathered by the organization "Public and Banks," the implementation of regulations has led to a substantial rise in the number of purchase agreements that include the right to redemption.[8] In practice, in order to enhance the enforceability of mortgage agreements and to seek a favorable interpretation from current regulations, there is a tendency to formalize the establishment of collateral through purchase agreements rather than mortgages. During this period, the property is transferred to the borrower's possession. If the borrower fails to repay the money within the agreed-upon period and is unable to return the funds, the property permanently becomes the lender's possession. In addition, if the borrower fails to make the interest payment during the agreed-upon period, the interest continues to accumulate in a manner that keeps the borrower's initial equity almost the same.

When utilizing this particular agreement type, the borrower will find themselves in an exceedingly vulnerable position. If they are unable to repay the loan within the specified timeframe outlined in the contract, they will ultimately forfeit their entitlement to the apartment. Consequently, they will be deprived of the ability to independently sell the property and thereby fulfill their obligations to the creditor. Given the challenge of ascertaining the intentions of the involved parties, the application of legal principles varies and it is not always feasible to identify a deceptive transaction. Consequently, the debtors became even more vulnerable, as they were unable to benefit from even the basic assurances that came with the official mortgage. Specifically, evaluating the ability to pay debts, utilizing credit insurance, and employing other similar methods within the official credit system safeguard the borrower who pledges his apartment as collateral from the potential threat of losing ownership. When the mortgage is camouflaged as a purchase agreement, it falls outside the mortgage regulations. In such a scenario, the debtor is left completely vulnerable and, in the event of non-payment, the loss of the property is assured.

In addition to the challenges mentioned above, it is important to acknowledge that both the legislation and the practice lack even the basic mechanisms for protecting and supporting individuals facing eviction. No state agency, whether at the central or local level, is deemed responsible for the obligation to prevent evictions and homelessness. It can be asserted that there is currently no preventive policy in place in the country to address this issue.

To prevent eviction and ensure adequate support for those who are evicted, it was crucial to implement the abolition of police evictions and incorporate a judicial component into the process. The court ought to be responsible for assessing the composition of families at risk of eviction, their socio-economic vulnerability, and the likelihood of homelessness. Its role would be to either prevent eviction or instruct the relevant authorities to arrange suitable alternative housing in case eviction occurs. Regrettably, the following issues are especially problematic in regards to the judicial mechanism:

The absence of minimum standards poses a direct challenge within the eviction process. The existing laws do not explicitly forbid evictions during winter, adverse weather conditions, or nighttime. Furthermore, there is no provision for the temporary suspension or termination of enforcement, considering the challenging socio-economic circumstances of the family or the specific composition of the family unit (such as the presence of a child).

One of the most pressing issues pertains to providing individuals with alternative housing following an eviction. The enforcement procedure fails to address the notification of eviction to the relevant authorities responsible for housing provision, and their involvement in the process is not taken into account. While some municipalities may offer specific services, such as apartment rentals or social housing, upon application to local authorities, however:

Regrettably, rather than collaborating to align eviction laws and policies with these standards, the government and parliament opt for a repressive approach toward their own vulnerable citizens, completely disregarding their duty to safeguard the right to adequate housing.

Hence, we firmly state that the state must implement a moratorium on evictions. We urge the government to immediately halt the eviction process for families residing in their only residence. Furthermore, we advocate for the government to collaborate with stakeholders and the public at large to develop a comprehensive, forward-thinking strategy to address this issue. This strategy should duly consider the welfare and rights of the population.

[1] For example, Orlic V. Croatia App. no. 48833/07 (ECtHR, 2011), par. 65; General Comment No. 7: The Right to Adequate Housing: Forced Evictions (art.11 (1)), Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1997, par. 14.

[2] Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context, A/HRC/37/53, 2018, par. 19; Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to nondiscrimination in this context, A/HRC/43/43, 2019, par. 38.

[3] General Comment No. 7: The Right to Adequate Housing: Forced Evictions (art.11 (1)), Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1997, par. 15; Council of Europe, Digest of the Case Law of the European Committee of Social Rights, 2022, p. 143.

[4] General Comment No. 7: The Right to Adequate Housing: Forced Evictions (art.11 (1)), Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1997, par. 13.

[5] General Comment No. 7: The Right to Adequate Housing: Forced Evictions (art.11 (1)), Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1997, par. 16.

[6] See, Pilot Project – Promoting Protection of the Right of Housing – Homelessness Prevention in the Context of Evictions, Full Report – Final Version, European Commission, 2016.

[7] See, article 625 of the Civil Code of Georgia. It should be noted that in the case of a mortgage, this indicator should not exceed one-twelfth of the 2.5 times the arithmetic average of the market interest rates of loans issued by commercial banks published monthly on the official website of the National Bank of Georgia, which is valid from the 1st of March each year.

[8] According to the information of the organization, from 2016 to 2018, the number of purchase transactions with the right of redemption registered was 1465, while in the period from 2018 to 2021, 11 132 such contracts were registered.

The website accessibility instruction