საერთო ცხელი ხაზი +995 577 07 05 63

Nino Chikovani

Professor, Head of Institute of Cultural Studies at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University

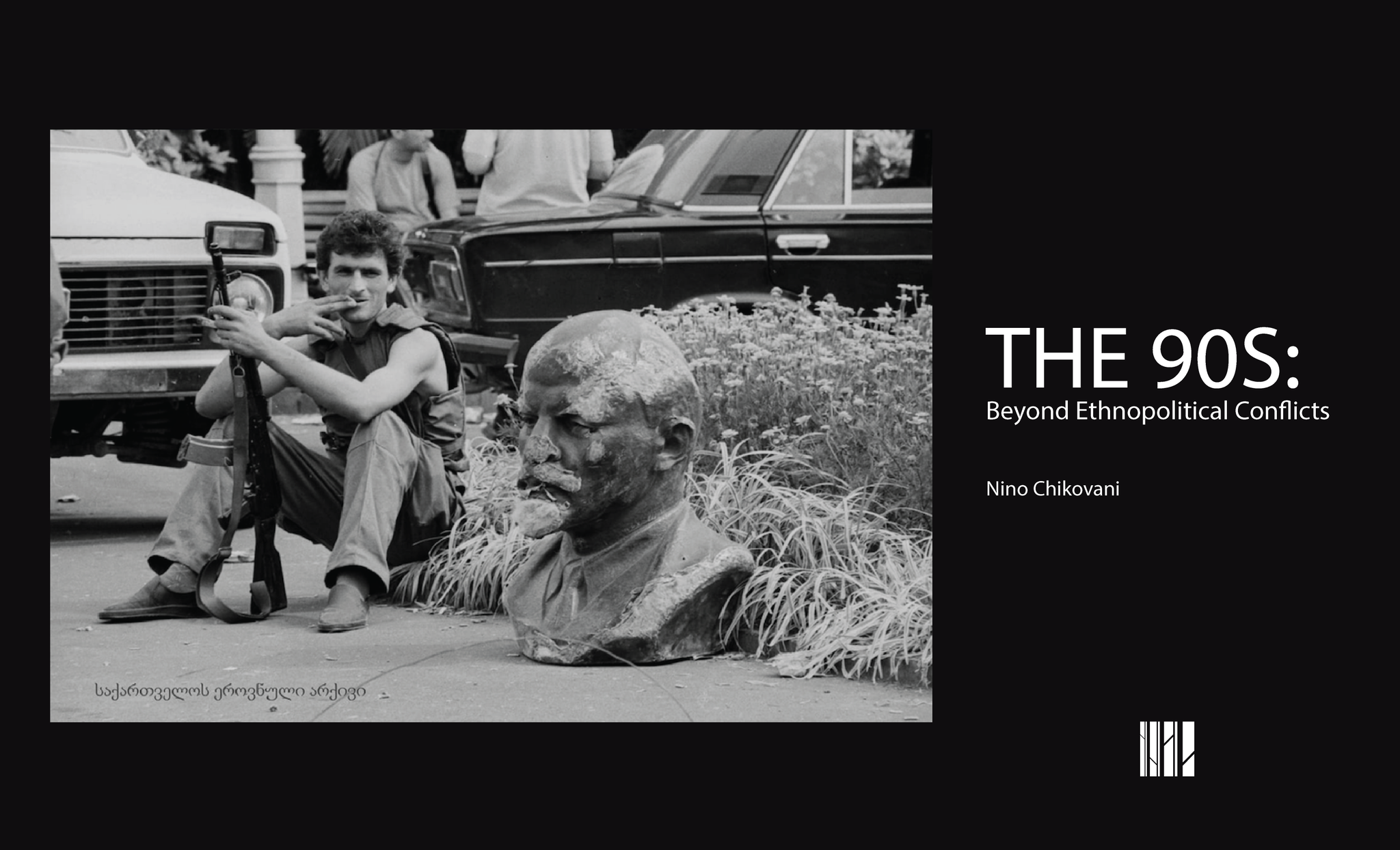

The beginning of the 1990s, especially its first half, primarily reminds us of the conflicts in Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region. The causes of these conflicts, the interests and involvement of internal and external forces, the results, and the ways of settlement are still subjects of debate. However, today, we will not delve into the conflicts themselves but rather explore the context in which they occurred and which hindered their understanding.

The purpose of this article is to analyze the complex and contradictory processes that unfolded in Georgia during the 1980s and 1990s. Some of these processes, accompanied by pain, gave birth to a sense of victory achieved through sacrifice, while others evoked feelings of shame or guilt, leading to a desire to forget. Certain events have firmly etched themselves into the collective memory, while others have served as the foundation for conflicting memories among different groups. These processes not only significantly shaped the country's future development but also continue to influence society today. Therefore, comprehending these processes is imperative for a complete presentation and explanation of the facts and events of the past 35 years.

The issues discussed in the article are understood in terms of the theories of collective memory and memory politics, which shed light on the dynamics of remembering and forgetting facts and events. In particular, Maurice Halbwachs' theory, Jan and Aleida Assmann's insights into the social nature of memory, Pierre Nora's and Jan Assmann's concepts related to the means used in the memory creation process, as well as the analysis of the theory and practice of memory politics proposed by these authors, enable us to gain a better understanding of the processes that unfolded in Georgia during the 1980s and 1990s, at the turn of the 20th century. Memory politics implies taking into account the fact that memory is selective, with facts and events from the past being conveyed and explained from the perspective of the present. Not only does the interpretation of past facts change, but the facts themselves are also "selected" for remembrance or oblivion. Consequently, narratives about the past undergo changes as well. Analyzing the current processes in the country from the perspective of memory politics helps us explain what we remember, why we forget, or why we may seek to avoid discussing certain aspects.

This work is based on extensive research supported by the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation, the results of which were reflected in the collective monograph "Georgia: Trauma and Triumph on the Way to Independence[1].

In the introductory letter to Guram Tsibakashvili's immensely important and captivating photo album, "On the Edge," Paata Shamugia succinctly and clearly describes the 90s as a kind of "symbol and conditional sign," which denotes not just a period in time, but a specific state, more precisely, an unstable transitional state.[2] A time of one type of system in the process of collapsing, and another - emerging towards a desired, albeit still vague, reality. For those who lived through this era and for whom "that time never ends,"[3]it is evident, even without specifying the century, which 90s we are referring to. However, it is likely understandable even for younger generations who have received knowledge of the 90s through communicative (and cultural, to some extent) memory."

Perestroika significantly weakened the prohibitions and restrictions imposed by the Soviet system. The policy of openness (glasnost) made it possible to start discussing previously taboo issues. The past, one of the most important foundations of collective identity, suddenly became the center of public attention. Spontaneously and sometimes quite consciously, it began to be revised, and a "new past" was constructed, intended to serve as a source of legitimacy for the new future.[4] One of the first steps on this path was the publication of a poem by the poet Kolau Nadiradze (1895-1991). This poem, written almost two decades earlier under the title "February 25, 1921," was published by the "Merani" publishing house in 1985 in a poetry collection dedicated to the upcoming 70th anniversary of the October Revolution. “With a red flag, with a singing voice, sitting on a white horse, death was approaching slowly, holding a scythe “[5]- - this is how the poet described February 25, 1921, which had been celebrated for decades as the joyful day of the establishment of the Soviet government in Georgia.

In the fall of 1987, as Georgia celebrated the 150th anniversary of Ilia's birth, the grave of the Georgian Bolshevik, revolutionary, and Soviet functionary Philipe Makharadze (1868-1941) was blown up in the Mtatsminda pantheon. His name, along with other social democrats, was associated with the murder of Ilia. Right next to Ilia, just a few meters away from him, he had rested since 1941. Scholars of culture and memory refer to this kind of attitude towards historical facts or characters as "reconciliation with the past" (Pierre Nora).

Starting in 1988, a wave of rallies and demonstrations swept through Georgia, not slowing down until April 9, 1989. In February, demonstrations began against the artillery explosion at the military training ground near the Davit Gareji Museum-Reserve;[6] In May, protests emerged against the construction of the Khudon HPP. On May 26, a rally was held to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the adoption of the Act of Independence of Georgia and the establishment of the first democratic republic;[7] In July, there was a rally against the construction of the Transcaucasian railway. The most extensive protest occurred in November 1988, featuring a hunger strike in Tbilisi directed against the amendment to the Constitution of the Soviet Union, which, at least nominally, allowed the allied republics to withdraw from the Soviet Union. Another astonishing incident took place during this time: one of the protesters pulled down the flag of the Georgian SSR that was flying atop the Government Palace building in front of the protesters and rally spectators.[8] On February 25, 1989, for the first time in Soviet history, mass speeches and rallies, with thousands in attendance, took place in the streets of Tbilisi. These events were held to protest the invasion of the Soviet army in Georgia in 1921 and the occupation of the country by Soviet Russia.[9] The young people removed the flags of Soviet Georgia displayed for the holiday and replaced them with the flags of the Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921)."

“We were born at rallies and were molded as a generation whose primary mode of articulation, expression of one's opinion, political will, or passions is through rallies. Our way of thinking, forms of communication, and behavior, even our manner of speaking, adopted the characteristics of rallies. Soon, these 'symptoms' of this 'condition' spread throughout Georgia and became the defining feature of the national identity as the people embarked on the path of self-determination," [10]wrote Giorgi Maisuradze two decades later.

April 9, 1989, marked the beginning of a significant chapter in Georgia's subsequent history. Just before this date, on March 18, 1989, during a congress held in the village of Likhni, Gudauti district, Abkhazia, an appeal was submitted to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The participants of the congress demanded the direct inclusion of the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Abkhazia into the Soviet Union, granting it the status of an allied republic. This demand stirred a negative reaction within the country, triggering a wave of rallies across Abkhazia and Georgia as a whole. On April 4, in front of the Government Palace in Tbilisi, initiated by Ilia Chavchavadze's society, a rally began with several thousand participants. Initially, it was focused on opposing Abkhazian separatism and its supporters. However, the rally quickly evolved as slogans emerged for the restoration of Georgia's independence and against the communist regime. Some of the crowd declared a hunger strike, demanding independence. The situation spiraled out of control for the communist government of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Georgia. In coordination with Moscow, the decision was made to disperse the rally. Additional military and internal troop units were deployed to Tbilisi. On April 8, they attempted to display force and intimidate the dissatisfied protesters by using military equipment in the streets of Tbilisi. However, this had the opposite effect, and on the night of April 9, even more people gathered near the government palace than on previous nights. At 4 a.m., without any warning, units of the Soviet Army and Internal Troops dispersed the rally using batons, shovel-like instruments, and poison. Sixteen people, mostly women, died on the spot, and four more protestors injured during the crackdown succumbed to their injuries in the following days. One young man was killed during the curfew. Several hundred poisoned and injured individuals were admitted to hospitals.

It can be said that the 90s started with this paradigmatic event. Society attempted to cope with the shocking tragedy that unfolded on Rustaveli Avenue through collective mourning and the open expression of emotions like pain, anger, and indignation. The narrative of April 9 blended elements of trauma and triumph, temporarily shifting the focus from the issue that sparked the rally on Rustaveli Avenue on April 4. The sacrifice convinced the mourning yet united and proud community of an inevitable future victory.

With the restoration of Georgia's independence on April 9, 1991, this belief materialized. In Zviad Gamsakhurdia's speech, the echoes of April 9 from two years prior resounded clearly: "The souls of the martyrs of April 9 are looking down and rejoicing in the heavenly light because their will was fulfilled, the will of the Georgian nation was fulfilled."[11] The traumatic aspect of the April 9 narrative was overshadowed by the joy of victory, once again underscoring the value of the sacrifices made for freedom: life overcame death, and good triumphed over evil. Many people gathered on Rustaveli Avenue, expressing their emotions through singing and dancing.

April 9 quickly became a date both tragic and triumphant in collective memory, taking its place among the 'glorious minutes' in Georgia's history. After the announcement of independence restoration, society was enveloped by the euphoria of triumph. People believed that the main obstacles had been overcome, the goal had been achieved, and the challenges of life could not undermine the significance of independence. Nothing could divert them from the path to success.

However, both April 9th events were followed by a series of severe natural and social disasters. Just ten days after April 9, 1989, on April 19, a landslide in the village of Tsablana in Adjara completely engulfed the village and claimed the lives of 23 people. Hundreds of families lost their homes, and over a thousand families were forced to relocate to villages in different regions of Georgia.

Another severe natural disaster struck in April 1991: a powerful earthquake on April 29, 1991, caused landslides, widespread destruction, and casualties in Racha, Imereti, and Shida Kartli. The village of Khakhieti in Sachkhere region was entirely buried, and all its inhabitants who were in the village at that time were killed in a rock avalanche.

In October 1989, Merab Kostava, one of the most prominent figures in the national liberation movement, died in a car accident. Immediately, doubts arose about the nature of the accident. Such a death of a leader with a difficult biography, unwavering in his commitment, and yet non-confrontational towards other factions of the national liberation movement and their leaders, on the one hand, solidified his image as a new hero and, on the other hand, raised concerns about the future relationships among various groups within the national movement. Merab Kostava's funeral at the Pantheon of Mtatsminda became another outlet for the emotions of a society still traumatized by April 9.

The situation in the autonomous units of Abkhazia and South Ossetia grew increasingly tense, and the threat of armed conflict escalated.

These social fractures and severe natural cataclysms created an overall traumatic atmosphere in the country that proved challenging to address. Influenced by the collective trauma of April 9, 1989, during which cultural patterns existing in Georgian reality were actively (and successfully) utilized, [12]including concepts such as sacrifice for the motherland, the necessity and inevitability of making sacrifices for victory, unity, strength, perseverance, endurance, belief in salvation, and destiny, the understanding of not only social changes but also natural disasters became intertwined with Georgia's tragic history. This inevitably led to the identification of an adversary, which, in the case of natural disasters, nature, providence, or fate would be considered as the enemy. Parallels were drawn with historical events, and victims of natural events were viewed as martyrs, akin to those who perished or were wounded on April 9. In newspaper publications, there were calls "for every Georgian to unite!" the statement typically used during enemy invasions. [13]This reflected the tradition of 'gaining strength in face of adversity'[14] and the hope for the future, as Georgians do not lose hope even in despair. “Algetian wolf cubs will grow up”, it was said[15]). After the tragedy in Racha and Zemo Imereti, discussions focused on destiny and the notion of punishment for 70 years of atheism, which was believed to artificially induce earthquakes. In this context, society attempted to explain the tragic events that befell them, imbuing them with meaning and addressing feelings of uncertainty and insecurity.

That's how the 90s began - the era of 'Van Damme, Chuck Norris, thugs standing on burning tires, militiamen with whistles, and thieves in white shirts; rampant robbers, alternative poetry, and entirely alternative rock.' When 'first there was a rally, then other things' emerged. Basically, it was all about politics. There were powerful speeches, cheers (in Georgian: 'gau-maaarjos-jos-jos), and the gripping, monotonous, exultant chant Zvi-a-di, Zvi-a-di. We even managed to live our lives in between political interludes. In its own way, of course.[16]

In December 1991, the section of Rustaveli Avenue, which one contemporary politician referred to as 'our Agora,' 'where the history of Georgia has been written for the past 30 years,'[17] became the battleground of the Tbilisi War. 'During the civil war, when the whole of Rustaveli was burning, the first thing that struck me strangely was that our flag was flying over the very Russian tank that chased us to kill just a year and a half ago, on April 9,' wrote Beka Kurkhuli in 2012.[18] Indeed, during the Tbilisi War and the subsequent civil strife that spread to different regions of the country, resulting in significant casualties, the sides faced each other with the flag that symbolized the tragedy and triumph of April 9. Over the next few years, this flag 'was in every war, and in every war, it went, it returned defeated everywhere, starting from Rustaveli Avenue, where it was on both sides and was defeated on both sides.'[19] The prevailing attitude could not be clearly defined. These events seemed suspended between forgetting and remembering. The opposing sides constructed conflicting narratives, with their attitudes toward the harsh experiences of the war remaining distinct even decades later. Questions about what happened, who the victims were, and who was guilty and responsible remained unanswered. The civil conflict, as a traumatic event, could not integrate into the cultural system of values. Eventually, hermetically sealed narratives emerged from the opposing groups. Even the name of this conflict was not agreed upon among different segments of society (civil war, putsch, struggle against provincial fascism, popular uprising, Russian intervention, and more). For supporters of Zviad Gamsakhurdia's government, the trauma, even after decades, could not be relegated to the past. Representatives of the opposing group tended to forget the painful past experiences and urged society to focus on the future. Some admitted their mistakes, but the other side questioned the sincerity of these statements. Hence, thirty years later, this war remains a source of division into opposing and sometimes irreconcilable groups, an event that periodically resurfaces in the present and 'feels like it happened yesterday.[20]

On August 14, 1992, during the acute phase of the civil conflict between supporters and opponents of the ousted President Zviad Gamsakhurdia, an armed conflict erupted in Abkhazia. The situation in the country became increasingly complex. One of the most traumatic experiences of the 90s was the emergence of a new social group resulting from the ongoing conflicts in Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region. These individuals were internally displaced persons, commonly referred to as IDPs, or 'refugees' as they were called in the 90s. Hundreds of thousands of citizens were compelled to leave their homes due to threats to their lives. Their resettlement occurred in a disorganized manner due to the chaotic situation in the country. Some sought refuge with relatives, while others were accommodated in hotels, sanatoriums, schools, hospitals, abandoned dormitories, and various other buildings in different cities across Georgia. These new dwellings were described as 'buildings fenced with wooden planks, plastic bags hanging over broken glass windows; damp and fungus-covered walls, crumbling ceilings; rusty pipes in the latrines, and, above all, people who were unable to maintain even basic hygiene, as they had been deprived of the opportunity to lead a dignified human life.'[21]This became the new reality for the majority of displaced individuals, a place they could never truly call home. In their new surroundings, marked by dire living conditions, the vast majority of IDPs, who had lost family members, their health, and social status, had to begin life anew in a country surrounded by economic, political, and social crises. Over time, the 'feeling of homelessness' evolved into a challenging emotional state for the displaced.[22]

Traumatized IDPs were welcomed by a society burdened with severe economic and social problems, and they, too, were traumatized. Initially, the IDPs received sympathy, and to the extent possible, assistance was provided to them. However, this sympathy and compassion couldn't be sustained for long. Gradually, IDPs became victims of stigmatization and indifference. They were perceived as others vying for jobs and already limited resources,[23] and, ultimately, the local community distanced themselves from them[24]. Thus, in the already fragmented society of the 90s, another dichotomy of 'us' and 'others' emerged as one of the constituents of the traumatic environment.

The triumphant mood of the early 90s was soon overshadowed by the constant stress induced by an all-encompassing crisis. State institutions were dismantled, crime proliferated, armed 'brotherhoods' and various military groups became a part of everyday life, and an economic collapse, food and energy crises compounded the problems. The situation that emerged after independence failed to fully align with the expectations of those who had dreamt of independence and fought for it. Access to education and healthcare, guaranteed pensions, stable economic and political life were among the unfulfilled hopes. The legacy of cultural customs and behaviors formed under the communist regime proved entirely dysfunctional in the new reality. This situation gave rise to anxiety, a pervasive sense of insecurity, mistrust of both other people and institutions, a crisis of collective identity, disorientation, apathy, passivity, and a pessimistic outlook on the future, intertwined with nostalgic recollections of the past.[25] Society, while gaining the long-awaited freedom, found its foundation shattered. All of these elements significantly shaped the form, symbols, values, and norms of social relations in the subsequent period. It was a form of collective or cultural trauma, brought about by a sudden, rapid, drastic, and fundamental change in the social environment, shaking the fundamental principles of social life and undermining the bonds that once unified society.[26] Piotr Stompka referred to this type of collective trauma as 'victory trauma,' signifying a change uniquely celebrated as a positive event. People had dreamt of it, fought for it, and made sacrifices, but when it materialized, it turned out to be too painful for the majority of society.[27] 'Victory trauma' has been experienced by many countries in the post-socialist space[28], though it was particularly distressing when internal conflicts were added to the existing political, economic, and social difficulties. Georgia is one such example.

The 90s in Georgia represent a period of 'victory trauma,' and the formation of the memory of this period is a complex and contradictory process. April 9 had the potential to be portrayed as an act of heroism and self-sacrifice, one that 'builds the image of the group's sacrifice as an honorable mission and gives meaning to future battles.'[29] This potential was realized in a narrative that combined elements of trauma and triumph, forming the basis for community consolidation.However, it proved challenging for not only the involved parties and their supporters but also for society as a whole to develop a collective attitude toward the Tbilisi war and civil strife. Lost wars are typically a difficult part of the past, but there is a distinction between these wars. Civil strife doesn't evoke a sense of pride. It cannot be forgotten, yet it is often avoided in the process of remembering.

Amid the backdrop of overlapping traumatic events, which left little time and space for reflection, the world appeared in stark black and white for a society preoccupied with survival and self-establishment. Ethno-political conflicts took their place in this complex chain of events—a significant part but still just one piece of the puzzle. This complexity made it more difficult and time-consuming for people to understand and contemplate how to cope with these issues."

[1] Chikovani, Nino, Ketevan Kakitelashvili, Irakli Chkhaidze, Ivane Tsereteli, Ketevan Efadze. "Georgia: Trauma and Triumph on the Road to Independence" (Tbilisi: Motherland, 2022).

[2] Shamugia, Paata. "Fahrenheit 90", Guram Tsibakashvili, on the edge. Georgia 1987-2000 (Tbilisi: Artanuji, 2019), p. 3.

[3] ibid.

[4] Foner, Erik. Who Owns History? Rethinking the Past in a Changing World (New York: Hill and Wang, 2002), p. 77.

[5] Poet's Thousand Lines (Tbilisi: Merani, 1985), p. 294. It should be noted that the poem is not mentioned in the contents of the collection.

[6] Mchedlidze, History without distance, p. 128-129.

[7] Ibid, p.130.

[8] History of Georgia, vol. 4, p. 496. This person - Gabriel Isakadze - was arrested and sent to a psychiatric clinic. see Mchedlidze, History without distance, p. 130.

[9] Mchedlidze, History without distance, p. 130.

[10] Maisuradze, Giorgi. "A holiday that is always with us," Giorgi Maisuradze, Closed Society and its Watchmen (Tbilisi: Bakur Sulakauri Publishing House, 2011), p. 5.

[11] "Zviad Gamsakhurdia - Declaration of Independence of Georgia," April 9, 1991, YouTube, March 31, 2017, https://bit.ly/3G4KP1f (viewed on February 10, 2021).

[12] Aleida Asman defines the cultural pattern as the icons deeply rooted in the memory of this or that unity, through which the members of the unity see, perceive and evaluate each other, give meaning to situations, experiences and events. Through them, it becomes possible to understand, comprehend, and determine the attitude towards non-existent, radically new and unknown events in experience (Assmann, Aleida. "Impact and Resonance - Towards a Theory of Emotions in Cultural Memory," The Formative Past and the Formation of the Future: Collective Remembering and Identity Formation, eds. Terje Stordalen and Saphinaz-Amal Naguib (Oslo: Novus Press, 2015), p. 43.

[13] Tukhashvili, Loward. "Adjara is calling us," The Communist, April 23, 1989, N 96, p. 2.

[14] Machavariani, Mukhran. "Stand strong Georgia," Rural Life, April 25, 1989, N 97, p. 1.

[15] Saginashvili, Tamar. "We need to stand strong amid grief, like a mortared stone" rural life, April 25, 1989, N 97, p. 2-3.

[16] Shamugia, Paata. "Fahrenheit 90", Guram Tsibakashvili, on the edge. Georgia 1987-2000 (Tbilisi: Artanuji, 2019), p. 3.

[17] Akofashvili, Zhana. "One year after Gavrilov's night - 'Shame Movement' is preparing for the June 20 campaign," Mtavari Arkhi, June 5, 2020, https://bit.ly/3n5yylU (viewed on February 3, 2021).

[18] Kurkhuli, Beka. "Drosha," Liberali, 30 October 2012, https://bit.ly/3tdn43x (accessed 16.01.2021).

[19] ibid.

[20] Volkan, Vamık D. When Enemies Talk: Psychoanalytic Insights from Arab-Israeli Dialogues, Zigmund Freud Lecture (Vienna: 1999), p. 14.

[21] Epadze, Keti. “Nameless Places,” February 3, 2021. https://16theelement.org/usakhelo-adgilebi/ (accessed 09/09/2023).

[22] ibid.

[23] Chankvetadze, Natia and Eliko Bendeliani. “From survival to self-sufficiency. Displaced Women in Georgia," Women during and after the war, ed. Tamar Tskhadadze (Tbilisi: Heinrich Boell Foundation, Tbilisi Office, 2020), p. 85.

[24] ibid, p.99

[25] Sztompka, Piotr. “The Trauma of Social Change: A Case of Postcommunist Societies,” Jeffrey C. Alexander et al., Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2004), pp. 165-166.

[26] Alexander, Jeffrey C. “Toward a Theory of Cultural Trauma,” Jeffrey C. Alexander et al., Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2004), pp. 1-2.

[27] Sztompka, Piotr. The Ambivalence of Social Change: Triumph or Trauma? WZB Discussion Paper, no. P 00-001 (Berlin: 2000), p. 21.

[28] Piotr Sztompka discusses it on the example of his homeland - Poland.

[29] Hirschberger, Gilad. “Collective Trauma and the Social Construction of Meaning,” Frontiers in Psychology 9 (10 August, 2018): p. 6.

The website accessibility instruction