საერთო ცხელი ხაზი +995 577 07 05 63

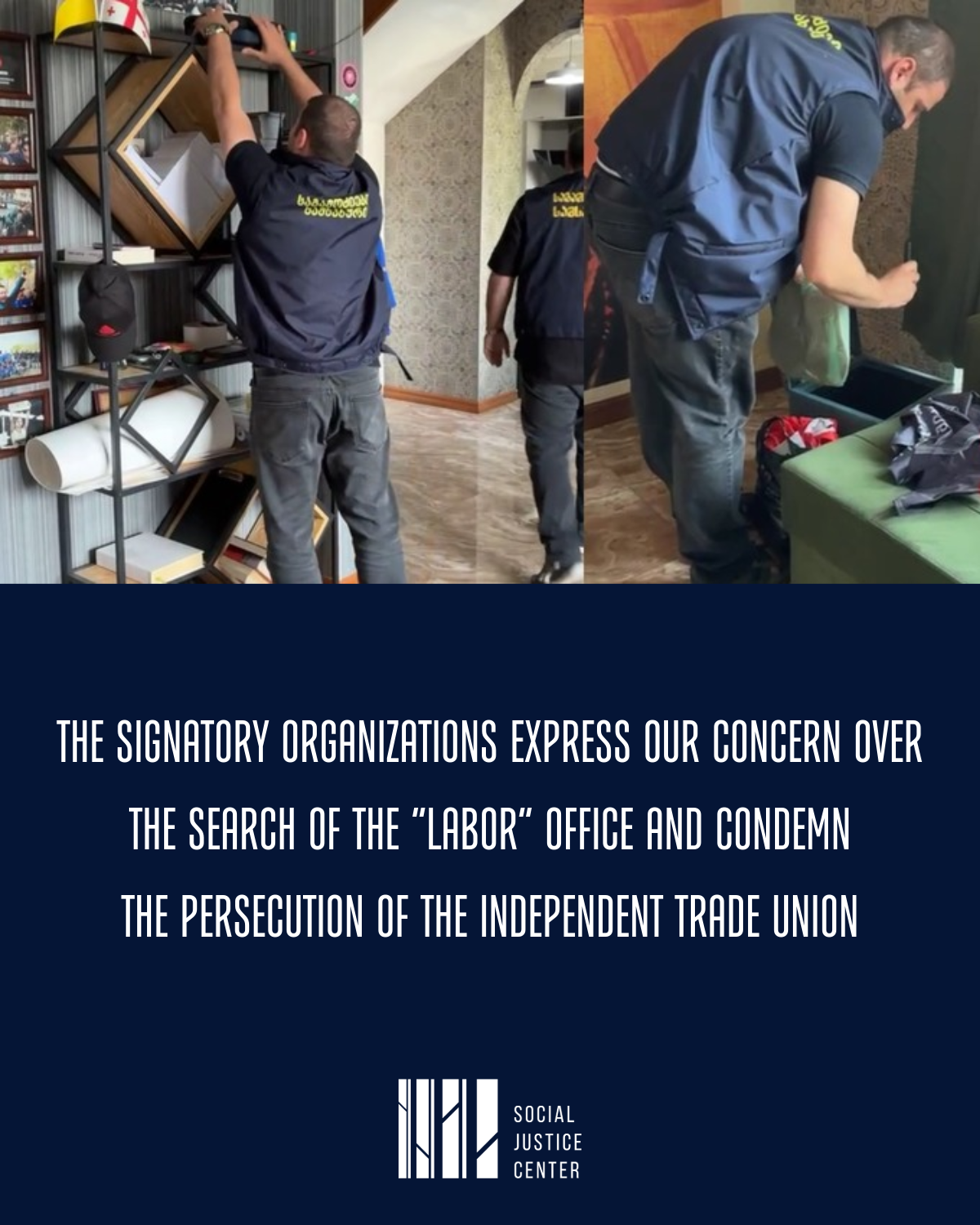

On April 24, representatives of the Investigation Service of the Ministry of Finance conducted a search at the office of the trade union “Labor”.[1] In addition to the trade union’s office, investigative actions were carried out at three other locations: the former office of the trade union, the residence of Chairman Giorgi Diasamidze, and the venue where the trade union’s congress had taken place a few weeks before the search.

The Investigation Service of the Ministry of Finance conducted a search of the office of “Labor” based on a ruling from the Tbilisi City Court. According to the trade union’s lawyer, this investigative action is part of a criminal investigation launched under Article 182 (3)(b) (Misappropriation or embezzlement committed in large amounts) and Article 362 (1) (sale or use of a forged document) of the Criminal Code. The actions taken against the trade union and its chairman lack sufficient evidence to support the investigation.

It is important to note that the search was preceded by the expulsion of the “Labor” from the Georgian Trade Unions Confederation in March 2025. This decision stemmed from the conclusion of the Trade Union’s Dispute Resolution Commission, which accused the chairman of “Labor”, Giorgi Diasamidze, of violating the Trade Union’s charter.[2] The Commission’s conclusion lacks an objective, fair, and evidence-based analysis of the case. This suggests that the Trade Unions Confederation is targeting the chairman of “Labor” for his criticism[3] of issues within the Trade Union, including its close relationship with the government. The persecution of Giorgi Diasamidze has now intensified through the use of state mechanisms, further compounded by unfounded investigative actions taken against him.

The trade union of agriculture, trade, and industry - “Labor”, has organized or co-organized approximately 20 strikes in Georgia in recent years, all aimed at improving the harsh labor conditions and socio-economic circumstances of workers.[4] These strikes include actions at “Evolution Georgia”, the Borjomi and Sairme mineral water bottling factories, and the flour production factory of LLC “Guria Express” in Ozurgeti. The ongoing strike at “Evolution Georgia,” which is organized by “Labor”, is the longest-running strike led by the trade union, having begun on July 12, 2024. It continues to this day,[5] with numerous employees participating. They have revealed a range of serious labor rights violations at the company, including unsafe and hazardous working conditions, unfair wages, excessively demanding work schedules, and insufficient time for breaks and rest.[6]

Various state agencies, including the Public Defender’s Office and the Personal Data Protection Service, have identified multiple instances of administrative offences committed by “Evolution Georgia.” In these proceedings, the employees’ interests were represented by the trade union “Labor.” In November 2024, the Public Defender’s anti-discrimination mechanism identified that “Evolution Georgia” engaged in practices that encouraged discrimination.[7] Additionally, in November 2023, it was found that the company violated its employees’ collective labor rights. These violations included various forms of interference with trade union activities.[8] Among these cases is also the October 2024 finding by the Personal Data Protection Service, which determined that “Evolution Georgia” had violated the requirements of the Law on Personal Data Protection in relation to the rules governing video surveillance in the workplace.[9]

It is important to note that the conclusion of the Trade Unions Confederation’s Dispute Resolution Commission, which led to the expulsion of “Labor”, addresses several issues. Among these is a complaint from a small group of striking workers at “Evolution Georgia”. The complainants allege that leadership of “Labor” has not adequately represented their interests. However, an initial assessment of the complaint suggests that it lacks substance and is not supported by any evidence to substantiate the allegations made.

Independent trade union activity, free from government influence and pressure from affiliated business entities - such as the “Labor” trade union - is essential for making real progress in Georgia’s challenging labor rights situation. The actions taken against “Labor” by state institutions and the Trade Unions Confederation represent persecution aimed at silencing independent and critical voices, violating fundamental rights such as freedom of association, trade union activity, expression, and speech. The establishment of a democratic state that prioritizes the social well-being of its citizens is unattainable without the full and unrestricted exercise of these vital rights. Their suppression is part of a broader pattern of systemic repression against free thought and anti-government protests in the country. The current government increasingly employs various intimidation tactics against the rising protest movement, civil society, non-governmental organizations, and independent media, utilizing repressive legislation and mechanisms of administrative and criminal prosecution. The list of targets is expanding, now including independent trade unions.

In addition to the fact that the search in the office of “Labor” clearly served repressive and punitive purposes from the outset, it is also important to highlight that several procedural violations were identified during the investigative actions.[10]

The Lack of Substantiation in the Search Warrant

A search is an investigative action that directly affects several rights protected by the Constitution of Georgia and international legal instruments. These rights include the right to property, the inviolability of private life, and in some instances, the right to dignity and honor. Therefore, such actions require prior authorization or confirmation by a court, except in cases of urgent necessity. In this case, the search of “Labor” was conducted based on a prior court warrant.

The Criminal Procedure Code of Georgia specifies the information that must be included in a search warrant.[11] Along with certain technical details and identifying information, the warrant must clearly state the probable item, object, substance, or material that is expected to be discovered and seized during the search, along with its general characteristics.

The law does not prohibit the seizure of items not specifically listed in a search warrant, including items that are prohibited from civil circulation, if those items are directly related to the alleged criminal act or indicate the commission of another crime. However, if the warrant does not contain specific details about the objects to be seized, it becomes very difficult to determine whether the investigator acted within the limits set by the court. Therefore, the investigator must justify the need to seize any additional items that are not listed on the warrant.

The Tbilisi City Court’s ruling on April 16, 2025,[12] which approved the search of the “Labor” office and other locations, fails to specify - even in general terms - the categories and characteristics of the items to be seized during the investigative actions. Issuing a search warrant in such vague terms undermines the prevention of unjustified restrictions on constitutional rights and diminishes the effectiveness of judicial oversight over investigative actions. Furthermore, the lack of information regarding the items to be seized in the court’s written authorization raises serious concerns about whether the standard for probable cause of the presence of those items at the specified locations was met. Therefore, it is clear that the Tbilisi City Court’s ruling authorizing the search did not comply with the requirements outlined in the Criminal Procedure Code.

In the case of Aliyev v. Azerbaijan, the European Court of Human Rights found violations of Articles 6 (right to a fair trial) and 8 (right to respect for private and family life) of the European Convention on Human Rights concerning searches conducted at the applicant’s home and office. The Court clarified that a national court’s decision must provide specific factual justification rather than solely making a general theoretical reference to the investigation of a criminal offence. Such a vague basis cannot justify an intrusion into a person’s private space. Additionally, the Strasbourg Court emphasized that a general and unsubstantiated judicial decision does not meet the standard of “reasonable doubt” necessary to justify a search regarding either the commission of a crime or the presence of relevant evidence at the location being searched.[13]

The Constitutional Court of Georgia states that while fighting crime is an essential constitutional interest, it is important to maintain a proper balance. This means that law enforcement can only limit an individual’s right to privacy when the investigative measures are genuinely aimed at solving a crime. Consequently, the Constitution allows law enforcement authorities to act only when there is a well-founded expectation - based on sufficient information - that significant evidence for the investigation will be obtained through the search. Conducting a search under circumstances where law enforcement lacks a well-founded expectation - supported by adequate information - of obtaining evidence significant to solving a crime cannot, by its nature, outweigh the harm caused to the right as a result of such an intrusive measure.[14]

Based on these interpretations, it is evident that both the investigative body’s motion and, more significantly, the court’s warrant cannot be deemed adequately substantiated if they do not articulate the necessity of the investigative action and its direct relevance to the alleged criminal offence.

The Unjustified Restriction of the Right to Record a Search

Criminal procedure legislation grants investigator the authority[15] to impose certain restrictions on individuals who are present at or arriving at the scene of a search. However, these restrictions do not include the right to record video or livestream the search process. Video recording of a search can serve as a vital safeguard, ensuring that representatives of investigative bodies do not exceed their legally granted powers. It also helps protect against the potential for items that do not belong to the searched individual to be improperly included among the seized items.

Using a livestream on social media instead of standard video recordings can provide an extra layer of protection for participants in an investigative action. This is because, even if investigators seize electronic devices, the live-streamed video material remains publicly accessible. Therefore, the restriction of the right to initiate a livestream can be considered legitimate only in exceptional cases, and only if the investigator provides a clear, specific, and lawful justification for such a limitation.

On April 24, the search of the “Labor” office was broadcast live on social media for approximately 15 minutes. According to statements from the trade union’s chairman and lawyer, investigators did not inform them before the search began that recording or livestreaming the investigative actions was prohibited. In fact, the livestream footage confirms that investigators explicitly allowed attendees to go live, provided that their faces would not be identifiable in the broadcast.[16] However, just a few minutes later, representatives of the Investigation Service of the Ministry of Finance demanded that the chairman of the trade union stop the livestream, without offering any explanation for this restriction or its necessity. As a result, the search continued for several hours without any video documentation.

The Restriction of the Right to Freely Leave Comments on the Search Protocol

According to the Criminal Procedure Code, once the search protocol is prepared, it must be presented for review to all participants involved in the investigative action (in this case, these participants include the chairman and the lawyer who were present during the search at the “Labor” office). They have the right to provide comments, suggestions, or corrections, which must be included in the protocol. Additionally, all remarks, suggestions, and corrections included in the protocol must be validated with the appropriate signatures.[17]

The law does not define the content of remarks. Any participant in a search must have the opportunity to include their comments in the protocol, regardless of whether the investigative authority agrees with them. According to the lawyer of “Labor”, when he requested to add a remark to the protocol (stating that he disagreed with its content, intended to legally challenge it, and noted that the seized items had not been sealed according to legal procedures) the investigator initially refused, insisting that he needed to know the content of the remark in advance. For about an hour, the investigator conducting the search did not allow the lawyer to make a comment and attempted to consult a supervisor about the matter. Eventually, the lawyer was permitted to write his remark. In response, the investigator added his comment, claiming that all items had been examined and sealed in accordance with the law. The lawyer then added a final note stating that he disagreed with the investigator’s comment.

Any participant in an investigative action has an unconditional right to leave a remark on the search protocol, and such remarks can be of significant importance. They can be used to legally challenge the protocol and, if charges are brought, help shape the defense strategy. A comment indicates that the individual disagreed with the protocol’s content from the outset. In the context of criminal proceedings, it provides the defense with grounds to file a motion to exclude any seized items from the body of evidence. Consequently, any obstruction by investigative authorities during the process of recording a remark is unjustified, contradicts legal requirements, and constitutes a serious violation of the right to a fair trial and the principles of equality and adversarial proceedings.

The Ineffectiveness of the Mechanism for Appealing a Search Warrant

Under the Criminal Procedure Code, a search warrant can be appealed once to the investigative panel of the Court of Appeals within 48 hours of its execution (the completion of the search).[18] The investigative panel then has 72 hours to review the appeal.

The trade union’s lawyer appealed the search warrant for the “Labor” office and other locations within the legally prescribed timeframe. However, the investigative panel of the Court of Appeals once again confirmed that judicial oversight of investigative actions is merely formalistic and ineffective. The decision issued in response to the appeal lacks substance and does not address the key concerns and problematic issues raised in the complaint.

In the appeal[19] filed by the lawyer of “Labor”, emphasis was placed on the vague nature of the search warrant and the lack of information regarding the specific items to be obtained. The appeal also highlighted the importance of adhering to the standard of reasonable doubt. Additionally, the complaint addressed the seizure of a personal computer processor from the trade union’s office, pointing out that the acquisition of electronic devices is regulated by a specific provision in the Criminal Procedure Code. Such seizures must comply with enhanced security standards. The law clearly states that the warrant must specify the physical or legal person from whom the information stored in a computer system or data storage medium is to be obtained, based on its general characteristics - including the particular computer system or data storage device from which the data is to be retrieved, as well as the presumed document or information to be extracted from that system or storage medium. Despite these clear legislative requirements, the search warrant failed to mention - even in general terms - anything related to the seizure of computer equipment.

Apart from general statements, the investigative panel of the Court of Appeals merely notes the existence of specific allegations concerning the trade union’s alleged misuse of funds and the submission of different congress protocols bearing the same dates to the National Agency of Public Registry. The court suggests that locations listed on the warrant may contain information relevant to the criminal case. However, the appeal court’s ruling fails to address several critical issues, including the absence of information in the first-instance court’s warrant regarding the items to be obtained, as well as the insufficiency of the facts presented in that warrant to establish a probable cause.[20]

The fact that the investigative body seized certain documents from the “Labor” office does not, by itself, indicate that the search was legal. The legality of a search is not determined by the materials obtained during the search - especially if those documents do not support the existence of any crime. Instead, the legality must be justified at the point when the prosecutor submits the motion for the search warrant. This principle was established by the Constitutional Court of Georgia in its decision on December 25, 2020.[21]

The facts outlined above clearly show that the search of the “Labor” office and other locations specified in the warrant did not serve the legitimate purpose of uncovering a criminal offence. The investigative actions were conducted in significant violation of the requirements established in the Criminal Procedure Code.

In the case of Leotsakos v. Greece, the European Court of Human Rights clarified that if there are significant procedural flaws during a search, investigative action cannot be deemed reasonable or proportionate, even if it aims to protect a legitimate interest, such as preventing crime. In this case, the Court found a violation of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which safeguards the right to respect for private and family life.[22]

In recent times - especially since the wave of continuous protests that began in November of last year - the use of criminal justice mechanisms against individuals and groups deemed politically inconvenient has become a systemic practice among those in power. The “Georgian Dream” party has increasingly relied on searches, interrogations, and questioning as tools for intimidation and discrediting aimed at silencing active participants in protests and broader civic movements. It is important to note that just days before the search of the “Labor” office, the trade union’s chairman, Giorgi Diasamidze, was summoned by the Financial Police for questioning related to the same criminal case. Due to a lack of trust in the authorities, he declined to appear and requested to be questioned in front of a magistrate judge.

The search carried out concerning “Labor” does not serve a legitimate purpose in investigating a criminal case or maintaining public order. Instead, it appears to be an attempt to marginalize trade unions from public life and represents yet another instance of the arbitrary and politically motivated use of criminal justice mechanisms. This approach undermines the very idea of the rule of law and promotes an authoritarian agenda of intimidation, persecution, and the suppression of citizens.

The signatory organizations condemn the persecution of the “Labor” trade union and express our solidarity with its chairman and all members.

Signatory organizations:

Social Justice Center

Independent Trade Union of Public Servants – “Article 78 of the Constitution”

Trade Union of workers in the field of culture - “Guild”

Trade Union of Science, Education, and Culture Workers

Georgia Psychological Association

Georgian Musicians’ Trade Union

Trade Union of Mediators

[1] Full title: Non-Entrepreneurial (Non-Commercial) Legal Entity - Georgian Trade Union of Workers Employed in Agriculture, Trade, and Industry.

[2] Decision of the Dispute Resolution Commission within the Georgian Trade Unions Confederation, February 7, 2025.

[3] Labor – Labor, April 4, 2025. Available at: https://cutt.ly/lrxoR74o.

[4] Labor, available at: https://cutt.ly/wrxoYwST.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Social Justice Center – “The Swedish side has initiated a preliminary review of the complaint submitted by the Social Justice Center against Evolution Georgia.” Available at: https://cutt.ly/NrxoIWS2.

[7] Public Defender Calls on Evolution Georgia LLC to Eliminate Practices Inciting Discrimination. Available at: https://cutt.ly/MrxoDwpW.

[8] Public Defender – General Proposal on the Prevention of and Fight Against Discrimination. Available at: https://cutt.ly/MrxoFXNs.

[9] Personal Data Protection Service, Decision No. G-1/295/2024, October 15, 2024.

[10] Note: In addition to publicly available media reports, the listed violations were identified through consultation with representatives of the “Labor” and a review of search documentation.

[11] Criminal Procedure Code of Georgia, Article 112, paragraphs 2 and 3.

[12] Tbilisi City Court Ruling of April 16, 2025, in case No. 11B/9416-25 (Judge: Nana Shamatava).

[13] ECHR, CASE OF ALIYEV v. AZERBAIJAN, (Applications nos. 68762/14 and 71200/14), 04/02/2019, 184.

[14] Constitutional Court of Georgia, Decision No. 2/2/1276 of December 25, 2020, in the case “Giorgi Keburia v. Parliament of Georgia”, para. 44.

[15] For example, under Article 120 (3) of the Criminal Procedure Code, the investigator may prohibit individuals present at the search or seizure site from leaving or communicating with others until the procedure is completed; such restrictions must be noted in the protocol.

[16] Livestream available at: https://cutt.ly/IrlCV8MX (Note: due to social media platform limitations, the livestream recording may no longer be publicly accessible after a certain period).

[17] Criminal Procedure Code of Georgia, Article 134 (5).

[18] Criminal Procedure Code of Georgia, Article 112(8) and Article 207(1).

[19] Complaint submitted by the representative of “Labor” and its chairman, April 25, 2025.

[20] Tbilisi Court of Appeals Investigative Panel Ruling of April 30, 2025, No. 1G/659-5, rejecting the complaint (Judge: Spartak Pavliashvili).

[21] Constitutional Court of Georgia, Decision No. 2/2/1276 of December 25, 2020, in the case “Giorgi Keburia v. Parliament of Georgia.”

[22] ECHR, CASE OF LEOTSAKOS v. GRÈCE, 04/01/2019, 57 (Only a press release is available in English).

The website accessibility instruction