საერთო ცხელი ხაზი +995 577 07 05 63

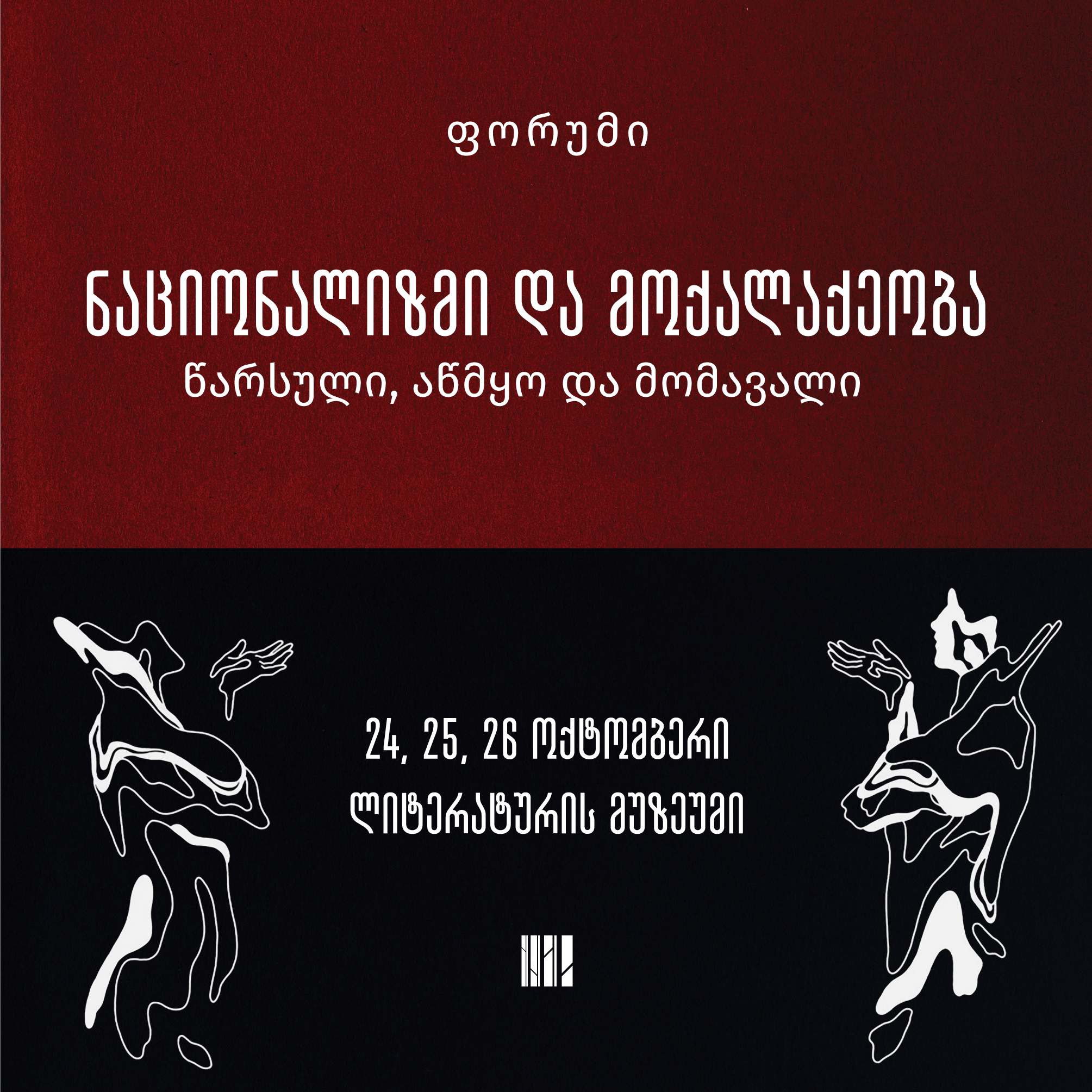

24, 25, 26 October, 2023

Address: Museum of Literature, Gia Chanturias 8, Tbilisi

The emergence of nationalism in Georgia can be attributed to the era of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. During this time, extensive state intervention heavily influenced the construction of national identity. This intervention played a significant role in shaping political identity and facilitated the establishment of hierarchies among nations and ethnic groups. The legacy from the 1990s, which continues to have an impact today, plays a defining role in shaping Georgian nationalism. This form of nationalism is characterized by its ethno-religious focus rather than a civil one. Furthermore, its exclusive and sterile nature frequently leads to societal tensions and the marginalization of ethnic and religious minority groups. In the early 1990s, Georgian nationalism manifested in notably extreme and suppressive manifestations, resulting in a distressing ordeal characterized by armed confrontations and acts of violence in certain regions of the country.

Throughout history, there has been a tendency to develop suspicion and negative opinions towards cultural groups not part of the dominant majority. These perceptions often label these communities as outsiders, posing a potential threat, or as diaspora members. These approaches not only give rise to symbolic and discursive hierarchies and demonstrate disdain but also result in the materialization and marginalization of non-dominant ethnic and religious groups, relegating them to second-rate citizens. Examining non-dominant groups' daily routines and experiences reveals a significant underrepresentation of these groups in politics. Additionally, they face more economic disadvantages, with restricted access to resources and possibilities for personal growth. Furthermore, their cultural expressions are inadequately represented in public spaces and mainstream culture. Notwithstanding this, our current state of affairs exhibits a distinctive occurrence of self-organization and activism within the communities of ethnic and religious minorities, aiming to broaden and enhance the prevailing understanding of the concept of nation. From this perspective, it may be said that the process of building a nation or political unity in Georgia remains incomplete and is undergoing continuous evolution in its substance and manifestations.

The post-90s crisis has eroded the faith in the concept of citizenship not only among non-dominant ethnic and religious groups but also among economically disadvantaged groups living in the reality of chronic poverty, deprivation, and inequality. The majority of citizens in the 1990s were unprepared for the rapid collapse, radical changes, and transformations that took place. The crisis that accompanied the transition evolved into a persistent and ongoing process, depriving daily life of its normalcy. There exists a dichotomous view of the post-Soviet populace, in which one segment of the population is characterized as resilient individuals with the aptitudes necessary for adapting to the changing system and recovering from a state of trauma. In contrast, the other segment is considered to be comprised of defeated citizens who were unable to succeed in this struggle due to their inability to satisfy the free market's demands. These individuals are viewed as lacking the required "diligence" to adopt "civilizational competencies." Certain academics have labeled this dichotomy as neo-Orientalism, when the defeated side is viewed as deficient in civilization. In post-Soviet societies, labeling substantially diminishes the power, political autonomy, and respect of a substantial portion of the population. In addition, it is sometimes used to justify the notion that authoritarianism, repression, and sacrifice are inevitable. Despite the self-organization and resilience demonstrated by our people, the established discursive hierarchies continue to function. It is apparent that the post-Soviet reality viewed through binary categories and approaches cannot adequately explain the internal paradox of life in this system, nor does this black-and-white logic of characterizing and classifying the post-Soviet citizen appear fair.

Within the framework of the 3-day forum, together with the invited academics and researchers, we will discuss the experiences of nationalism, citizenship, subordination, and resistance in Georgia and create an interesting space for critical and collective thinking and dialogue on these issues.

Agenda

Topic of The Day: Georgian Nationalism Today – How did we end up here?!

16:30 - 17:00 Registration

17:00 – 17:15 Welcome Speech and opening remarks

17:15 – 18:30 Panel Discussion:

Georgian Nationalism Today – How did we end up here?!

Speakers:

18:30 – 19:00 Q&A session

19:00 -19:30 Coffee Break

19:30 – 20:30 Keynote Speaker (online presentation):

Ronald Grigor Suny, Professor of History and Political Science at the University of Michigan and Emeritus Professor of Political Science and History at the University of Chicago.

20:30 – 21:00 Q&A session

Topic of the Day: Disputed Citizens - Excluded Majority

16:30 -17:00 Registration

17:00 – 18:30 Panel Discussion:

Disputed Citizens - Excluded Majority

Speakers:

18:30 – 19:00 Q&A session

19:00 – 19:30 Coffee Break

19:30 – 20:30 Keynote Speaker:

Michal Buchowski, Professor of Social Anthropology, University of Poznań.

20:30 – 21:00 Q&A session

Topic of the Day: Nationalism and the Exclusion of Non-dominant Ethnic and Religious Groups in Georgia

16:00 -16:30 Registration

16:30 – 18:00 Panel Discussion:

Nationalism and the Exclusion of Non-dominant Ethnic and Religious Groups in Georgia

Speakers:

18:00 – 18:30 Q&A session

18:30 – 19:00 Coffee Break

19:00 – 20:00 Keynote Speaker:

Krista A. Goff, Historian, Associate Professor of History, University of Miami.

20:30 – 21 :30 Q&A session

21:30 – 21:30 Concluding Remarks

The website accessibility instruction