საერთო ცხელი ხაზი +995 577 07 05 63

Anatoly Reshetnikov is Assistant Professor of International Relations at Webster University.

In the bygone year of 2015, Russian human rights NGOs launched a documentary project about human rights defenders. Despite the fact that, one year earlier, Vladimir Putin had already annexed Crimea, while Boris Nemtsov, an important opposition leader, was shot dead in front of the Kremlin in February 2015, the times were still relatively vegetarian in Russia. A few political assassinations, a handful of political prisoners, and the foreign agent law adopted in 2012 – even though all extremely alarming back then – could not compare to what was yet to follow.

Therefore, a large-scale web-documentary about Russian human rights organizations did not only have a vibrant community of outspoken personalities and organizations to converse with, but also made perfect sense as an educational project. The human rights community believed – and rightly so – that regular Russian citizens simply did not know enough about their daily activities and, as a result, easily bought into the bogus foreign agent rhetoric. Far from being some kind of conscious agents of any foreign influence, most human rights NGOs were, in fact, surprisingly apolitical (at least, in their public stance) and simply worked with the people who found themselves in very difficult life situations: from young conscripts and prisoners to drug users to refugees. And, since the Russian state had very limited resources to take care of its marginalized and dispossessed, sometimes those NGOs had to rely on international funding, yet never bindingly or exclusively.

The project was supposed to demonstrate to regular citizens, but also` to the state, that there was nothing conspiratorial or politically subversive about human rights work. Activists were simply trying to patch the holes in the imperfectly implemented legal system, which, in fact, had been formally grounded in human rights principles, but, as the time passed, deteriorated and slackened. Instead, however, the project became a chronicle of a methodical extermination attempt of the Russian civil society.

Strategic responses to the foreign agent status

Mostly focusing on those NGOs that had recently been labelled foreign agents, the project team documented meticulously their daily struggles, routines, and self-reflection about the new legal, political, and social environments. Having many trained lawyers in their ranks, Russian human rights NGOs tried to approach the new situation very pragmatically. They applied their best legal judgement and sensibility to find out possible ways to continue their activities and to avoid mistreatment or repression by the state apparatus. After all, a major share of their daily work involved tedious and, when possible, constructive communication with the authorities, from courtrooms to detention facilities to immigration centres.

Responding to the imposed stigma, some NGOs, such as Andrey Rylkov Foundation protecting the health and human rights of the victims of the war on drugs, tried to follow the new rules and accepted the burden of ubiquitous and mandatory public self-labelling as a foreign agent. They continued their work in Russia even after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, but, in the words of the Foundation’s director Anna Sarang, they were “totally left without any financial or moral support,” because the international funding bodies mostly “gave [Russia] up as a hopeless case.”

Other organizations, like Crew Against Torture, which documents and fights against the instances of torture by the police in Russian prisons and detention facilities, initially tried to play hide-and-seek with the authorities. From 2015 till 2022, different legal avatars of the organization were included into the foreign agent register at least four times. Every inclusion led to an eventual liquidation of the respective organization. While the new avatar of this NGO is still afloat and active as Crew Against Torture, today they have to comply with the discriminatory law and publicly self-label as foreign agents. Still, despite the existing barriers, the NGO continues their important work on the ground.

Another influential NGO, “Soldiers’ Mothers of Saint Petersburg,” who defend human rights of conscripts and monitor human rights violations in the Russian army, tried to question the legal design of the new law, criticising the absence of a clearly specified legal mechanism that would allow a foreign agent to forego their status. Among all Russian human rights NGOs, the Soldiers’ Mothers of Saint Petersburg were a rare exception, as they managed to get rid of their foreign agent label as early as October 2015, after they renounced all foreign funding, tried to find alternative domestic resources, and applied significant legal pressure to have themselves excluded from the list.[1]

This fact, however, did not shield the organization from further intimidation and monitoring by the authorities. Allegedly, in October 2021, just a few months prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and in response to a recent regulation by the Federal Security Service (FSB), Soldiers’ Mothers of Saint Petersburg decided to stop some of their monitoring activities. The activities they decided to drop included the evaluation of “lawfulness and the moral-psychological climate in the army,” that, according to FSB, would count as a typical foreign agent activity. Instead, Soldiers’ Mothers are currently trying to apply their expertise in other formats, increasingly so – offline, and much less actively than before due to financial strain and their unwillingness to be relabelled as foreign agents.

Targeted strikes and let live cases

Arguably, the Human Rights Centre Memorial, a broadly focused human rights organization, was hit the hardest becoming a target of pinpointed political repressions. Multiple police searches and arrests of its members forced many (if not most) Memorial employees to move abroad where they are now trying to regroup and continue their activities in different formats. The Russian NGO itself was stroke off the register and now continues its operations without any legal entity as Memorial Human Rights Defence Centre. The Chair of Memorial’s Council, Oleg Orlov, who served a sentence in Russia for allegedly “discrediting” the Russian army, became part of the major prisoner exchange between Russia and the West that took place in August 2024. In a recent interview, Orlov admitted that the stigma of a foreign agent severely complicates human rights work, virtually pushing it underground and removing publicity as a viable strategy from an NGO’s toolkit. At the same time, he insisted that human rights defenders remain active in Russia, even if their work’s efficiency has diminished, while their activities mostly comprise information gathering and whistleblowing.

For instance, Citizens’ Watch, an NGO that was listed as a foreign agent, but still remains active in Russia, continues to perform their routine monitoring of court cases, as well as prepare reports both for international organizations and for Russian courts. In those reports, Citizens’ Watch document the violations of human rights in various legal areas, from judicial harassment against LGBTQ+ and racial profiling to the violations of detention conditions. While the NGO’s employees have no illusions regarding any immediate effect of their activities, they still hold the position that Russia’s exodus from the international legal frameworks is temporary and that their work would prove crucial during the future reintegration. Just like Andrey Rylkov Foundation, Citizens’ Watch chose to comply with the discriminatory foreign agent law and try to self-label themselves in all recent publications in Russian.

A systemic view

According to Bederson and Semenov’s analysis, the state applied three types of pressure on the NGOs labelled as foreign agents: (1) financial pressure in the form of high monetary fines for violating the regulation; (2) supervisory pressure exerted through constant unscheduled inspections and audits; and (3) reputational pressure comprised of public labelling that often led to the stigmatization of NGOs and the growing unwillingness of bureaucrats and the broader public to cooperate with foreign agents. All three kinds of pressure were traumatizing for Russian NGOs who normally did not have access to unlimited financial and human resources. Yet, depending on the amount and variety of available resources, one could notice that the organizations’ responses to stigmatization varied accordingly.

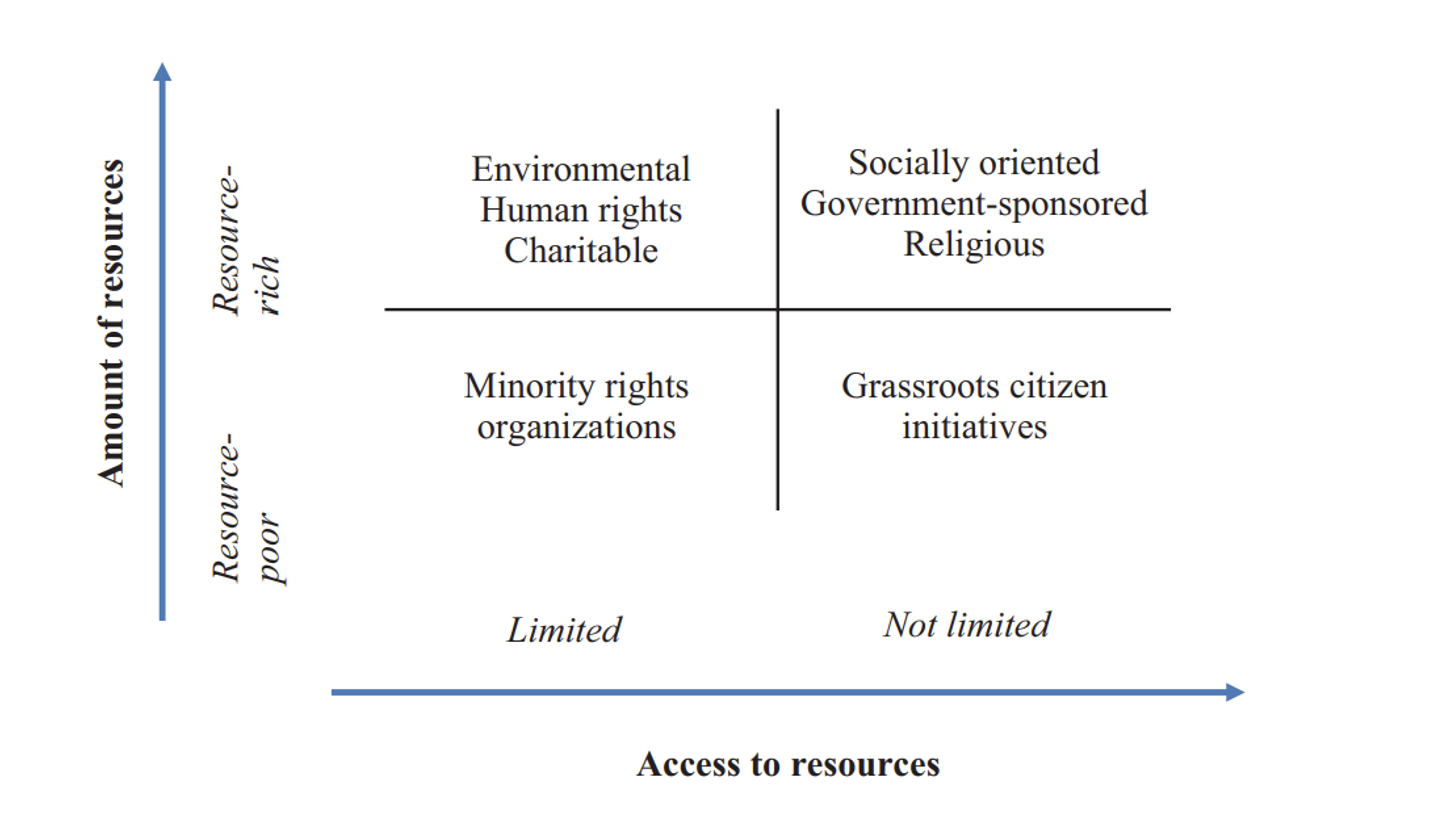

Using the classification of organizations by volume of and rules of access to resources, Bederson and Semenov distribute different types of NGOs among the four niches (Figure 1). To contextualize the two depicted dimensions, “resource-rich vs. resource-poor” axis represents the difference between subject areas, where a lot vs. very few institutional donors exist, while alternative sources of funding (e.g., crowdfunding) are easily mobilizable in “resource-rich” side of the axis vs. hardly plausible in the “resource-poor” side, which may happen for various reasons (e.g., when an issue is not considered important by donors and broader public). The “limited vs. not limited” axis conveys whether or not the state imposes strict legal and institutional frameworks regulating or restricting access to available resources. As a general rule (and also in Russia), in terms of their access to resources, different kinds of NGO and grassroot initiatives are distributed along those axes as pictured in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Classification of organizations by volume of resources and rules of access (Source: Vsevolod Bederson and Andrei Semenov, "Between Autonomy and Compliance: The Organizational Development of Russian Civil Society."

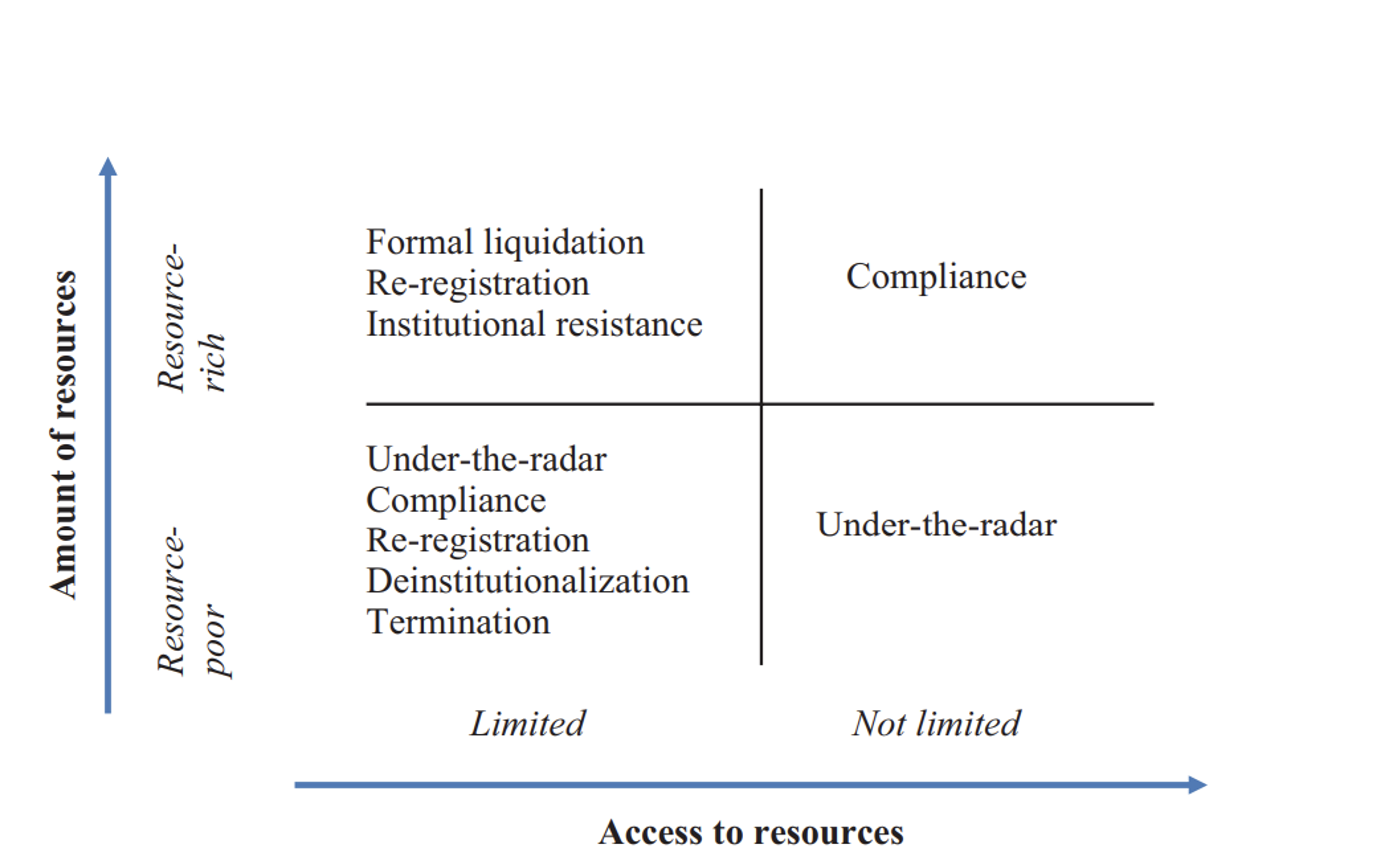

The volume and diversity of available resources, as well as the state-imposed rules of access to those, conditioned alternating responses of Russian NGOs to the adoption of the foreign agent law, as well as to the imposition of this label upon specific organizations (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Organizational responses (Source: Vsevolod Bederson and Andrei Semenov, "Between Autonomy and Compliance: The Organizational Development of Russian Civil Society.")

Some NGOs that were confident about the variety and continued availability of resources due to their close relationship with local authorities and the general possibility to receive state funding had to make compromises and chose compliance as their main response option. They followed carefully the letter of the law and both self-labelled as foreign agents wherever they were expected to and, simultaneously, tried to forego their foreign funding sources, hoping to adapt to the new environment. Other organizations that operated in the resource-poor subject areas but managed to establish some rapport with local authorities preferred to stay under-the-radar to avoid being labelled as foreign agents. In practice, this meant that they could implement their low-key social projects using the meagre funds they had access to, but dropped the idea of applying for foreign grants. Naturally, this either stopped, or slowed down their growth and development, as well as hindered their professionalisation.

Both compliance and under-the-radar strategies were also utilized by some NGOs, which worked within resource-poor subject areas and relied on the resources that were strictly regulated by the state (e.g. foreign grants). In the case of compliance, this implied investing a lot of human resources into preparing to withstand the three mentioned types of pressures and to react swiftly to every frequent amendment of the foreign agent law, without rejecting foreign funding. Those, who preferred to stay under-the-radar, could try to implement some very low-key initiatives funded from the restricted funding sources without making too much fuss.

In general, however, the NGOs working in the resource-poor and limited access niche struggled the most. When compliance was not a viable option, due to limited financial and human resources, while the attention of the authorities had already been drawn, these NGOs only had three other strategies to choose from the Bederson and Semenov’s response assortment: (1) re-registration (i.e., changing the legal avatar); (2) deinstitutionalization (i.e., reducing drastically the scale of operations); and (3) termination (i.e., ceasing all activities and letting go of all the volunteers and staff). Neither of the three strategies proved beneficial for the NGOs that adopted them. Those who chose to re-register, like the previously mentioned Crew Against Torture, but also the electoral watchdog Golos, were eventually forced to comply. Those organizations that deinstitutionalized or terminated themselves naturally had to either shrink their activities to the bare minimum they could afford, or disappear completely.

Finally, the NGOs that operated within the resource-rich subject areas, where access to resources became heavily regulated by the state, could either try (1) to re-register (to clear their reputation); (2) to perform a formal liquidation (and remain active as an informal activist group); or (3) to develop institutional resistance mechanisms (i.e., to fight to preserve the organization in the court of law and have it excluded from the foreign agent register). Here again, neither of the three strategies is ideal. Re-registration of some organizations (such as Agora) operating within the resource-rich environments with limited access eventually led to further criminalisation (as an “undesirable organization”; see the next section for other related examples). Formal liquidation naturally reduced the scope of activities and the outreach of those NGOs. Institutional resistance occasionally proved effective, but was extremely costly and time consuming, which diverted the organizational resources from other important tasks to endless legal battles about the foreign agent status (Soldiers’ Mothers of Saint Petersburg would probably be a good case in point).

Worse than foreign agents

As the examples discussed above show, in most cases, the label of a “foreign agent” works as a tool of intimidation and a stigma. Indeed, according to existing research, autocrats are often not so much interested in the complete suppression of civil societies. Instead, they are looking for complete control over seemingly independent NGOs that could be utilized for regime legitimation purposes. However, once the scope of the Russian foreign agent law was broadened to include private individuals, this stigma was often imposed, among others, on journalists, bloggers, actors, musicians and writers who said or wrote anything that the Kremlin did not like. As a rule, in addition to bureaucratic burden, the foreign agent status also meant that bloggers and public personalities would lose most of their advertising income, while actors and musicians would lose their concerts and roles (at least in Russia). Still, if the stigmatized chose to comply, the foreign agent status did not necessarily lead to criminal cases or imprisonment. Rather, it merely silenced those who were labelled and complicated their lives. At the same time, for the oppositionally-minded Russians, it sometimes even served as a mark of honour, imposed on those individuals and organizations that did something important to defend human rights and oppose authoritarian tendencies.

Thus, to address what was perceived as more tangible threats, the Russian regime developed harsher and more effective legal tools, relying on the sections of the Russian legislation devoted to extremists, terrorists, and “undesirable” organizations. Perhaps, the most well-known case of using such labels against the regime’s political opponents was the ousting of Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation from Russia, which forced most of its employees to leave the country and was followed by the alleged murder of Navalny himself. However, some human rights NGOs also did not avoid a similar fate. For instance, shortly after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the environmental rights NGO “Bellona”, which is headquartered in Norway, but was very active in Russia, was put on the list of “undesirable organizations” and chose to cease their work in the country, as well as to help all their local employees with relocation to the EU. The new status threatened anyone who had any dealings with the NGO with potential criminal liability. Meanwhile, Bellona kept their eyes on Russia and continued publishing reports about the nuclear aspects of the Russia-Ukraine war, as well as the environmental consequences of this conflict.

Future outlook

To conclude, in the last ten years, once vibrant Russian civil society shrank significantly in size with many activists having to leave the country or forced to remain silent. One of the most important instruments used by the state to carry out such civic cleansing was the foreign agent law adopted by the Russian Parliament in 2012. The law, which was originally targeting non-profit organizations receiving funding from abroad, progressively expanded its scope and started to be applied to media platforms, unregistered associations, and even private individuals, serving as a tool of discrimination and selective punishment for Putin’s regime. Human rights NGOs that were the first who got hit were followed by multiple other individuals and organizations. From 2022, the law could be applied to anyone, who was believed to be under “foreign influence”, whatever it is supposed to mean. Despite such gloomy developments, there is also some hope. Even though human rights work became exceedingly difficult and often ineffective in Russia, some parts of the local human rights community are still holding. The important work is being done continuously, even if often covertly, while its methods resemble more and more the methods of Soviet dissidents.

[1] According the Russian Ministry of Justice, as of September 2024, 209 persons and entities were taken off the foreign agents register, which amounts to 25% of all those that had been previously included into the list. Out of those 209, in 71 cases the exclusion took place by request of foreign agents themselves.

The website accessibility instruction