საერთო ცხელი ხაზი +995 577 07 05 63

Gota Chanturia is a PhD student at East European University,

Director of the Education Coalition

Perhaps most of the readers thought that the text above accurately reflects the current reality in the education system. In principle, this is true, but interestingly the given text is a fragment from the 2012 election program of the Georgian Dream, in which the policy of the United National Movement is described.

In this article, I will try to analyze the 12-year education policy of the Georgian Dream (mostly general education) and highlight its main features and errors. Obviously, it can be written a lot and in many ways, but since this is not an academic article, I will write "whatever comes to my mind and as it comes to me."

Education as a tool of empowerment

When the Georgian Dream came to power, one of the main promises was to strengthen the autonomy of the education system and reduce ruling party pressure. In this regard, a special commission was created in 2012 to study the cases of employees dismissed for political opinions in the education system (see the report of the commission). In addition, the reform of the bailiff service created during the time of Dimitri Shashkin (whose period of ruling can be considered as one of the toughest) has also started. Nevertheless, it was difficult for the government to reduce control over schools and give them autonomy. For example, State Order N837 adopted in 2010 is still valid, according to which, without the permission of the Ministry, schools are restricted from cooperating with both physical and legal entities. At the same time, those who were responsible for its control during the previous government still remain in the system. For example, the Deputy Minister of Education, Gela Geladze, who was one of the heads of the Resource Officers during the tenure of Dimitri Shashkin, and previously worked in law enforcement structures.

Another mechanism of control over the schools was the selection process of the school principles. Unfortunately, the recent period has clearly shown that since 2020, this tool has been used for this very purpose, and the process, despite a lot of criticism, has been completely opaque (see the statements of the Education Coalition and public organizations). As a result, we are seeing increased pressure on principals and teachers to engage in activities that support the ruling party - Georgian Dream. This pressure is especially strong when there is no real trade union in the country, an institution that would, on the one hand, protect and, on the other hand, promote the issues of teachers' rights in the public agenda.

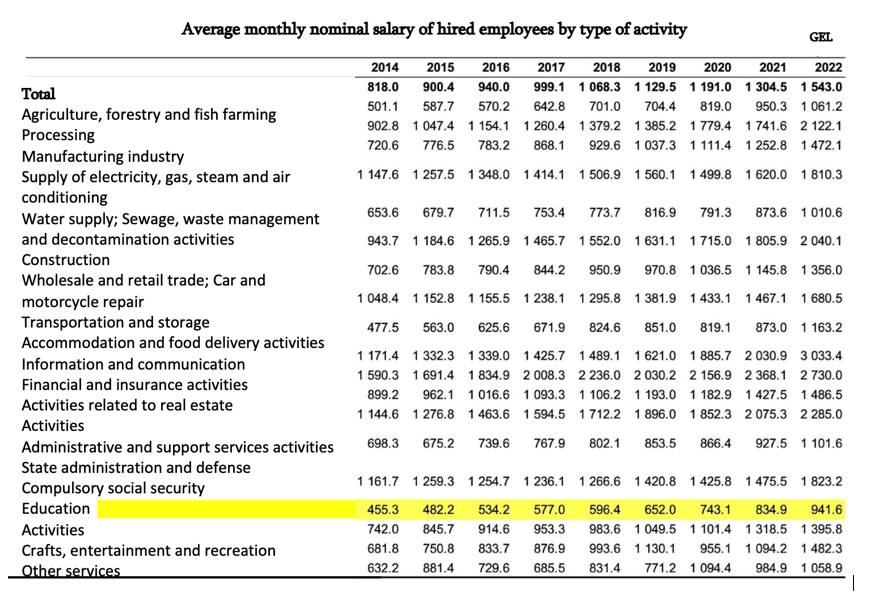

It is noteworthy that despite many promises, the working conditions and social condition of teachers have not actually improved under the conditions of the Georgian Dream. As of 2024, the education sector has the lowest salaries compared to other sectors.

Source: GEOSTAT

The idea and function of education

It should be clear to the readers that the education system is governed by party goals instead of educational goals. But what are the goals of education itself, and how are they perceived by decision-makers?

According to American educator John Dewey, the goal of education is education itself (Noddings, 1995). Gert Biesta (2009) singles out three main goals of education: first, qualification, which means imparting knowledge, developing skills, and competencies; second, socialization, where the education process helps us become members of society; and third, subjectivization, which promotes individualism, autonomy, and independence.

In addition, we should consider education as a tool for social progress, and educational institutions as institutions with an important social function. Among these functions is for example community development. If we look at the education system from this perspective, it becomes clear that it cannot fulfill its role and function.

In recent years, discussions on the subject of education have been scarce and in fact never encouraged. However, these types of discussions are important both for the development of the education system and the society itself. For example, you will often hear from teachers the phrase: ‘We are preparing students for the future.’ In principle, there is nothing wrong with this phrase, but you will almost never hear that the purpose of education is not only to focus on the future, but also on the present. Similarly, you will hear the phrase that the school should be free of politics.[1] To give another example, some time ago we saw the statement of the rectors of the universities, in which they echo the protest against the ‘Russian law’ and call the university a "politics-free" space. The continuation of the same policy was issuing the threat letter by the National Center For Educational Quality Enhancement to higher educational institutions. Fortunately, the letter backfired on the Ministry, as the majority of the Center's employees dissociated themselves from the statement. At the school level, it was even more alarming when the deputy of the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, Lado Mgaloblishvili appealed to the parents to report on those teachers that talk about politics to students. Each of these examples clearly shows the wrong and narrow understanding of the Georgian Dream regarding the purpose of education and educational institutions. Accordingly, the policy change regarding education should start with discussion on the goals and purpose of education.

Education as a market

In an article about the marketization of the education system (2014), Maya Chankselian writes that in 2012, during the ministry of Dimitri Shashkin, the education system reached the high point of marketization. This is the system adopted by the Georgian Dream, with which, in principle, it had no ideological opposition.

Marketization, to put it simply, is basing the educational system on the principles of the market economy and the guidance by these principles. For example, in the rhetoric of almost all ministers, you will hear that raising a ‘competitive citizen’ was their main goal, which in recent years has been replaced by ‘human capital development’. In this system, the student/pupil is perceived as a ‘product’, and education as a ‘service’, which if you can't buy from one place, you'll go and get it elsewhere.

|

Text: in the kitchen of the ministry: Ministers: Colleagues, today we will discuss the national goals of general education. Let's start with this: what don't you like about students today? Employees: They lack respect for family; They are not ready for a decent life; I think there are too many liberties; Another thing is that they are hungry; They are rude to the representatives of the state institutions. Ministers: Good, great! How many things are to be changed! But we forget one thing. Well, who's to say? It starts at C… Our students are missing… Employees: creativity? Conformism? sewage? Cotlet? Ministers: Competitiveness colleagues. Employees: Aha. |

Photo: Facebook page ‘new whip’(ახალი მათრახი)

Some researchers refer to such systems or reforms as an ‘epidemic’ (Levin, 1998), which ultimately leads to institutional, individual, and value system schizophrenia (Ball, 2003). Lyotard calls this the ‘law of contradiction’, when instead of priority issues, focus is placed on secondary issues. For example, in the case of teachers, when they are not focused on teaching-learning, developing curriculum or cooperating with each other, but on presenting an image or accumulating so-called credits. In the case of universities, the focus is on marketing and attracting students instead of research. Georgian Dream policy is characterized by such managerialist approaches, where professionalism, experience and cooperation are secondary.

Lessons of (in)equality

When evaluating the education system, one of the main criteria is equality - how much does the state create equal conditions for students? To what extent does it give them equal opportunities?

To be fair, it should be noted that in the first years of governance, Georgian Dream started implementing programs focusing on elimination of inequality and supporting vulnerable groups. For example, free textbooks and student transportation programs, sending qualified teachers to regional schools to offer them better conditions ("Teach for Georgia" program). In addition, important steps have been taken in the development of inclusive education. As a result, if in 2019 160 students were registered with special educational, this number became 1,613 by 2013, and by 2019 - exceeded 7,000 (Chanturia, Kadagidze, and Melikadze, 2020)

Nevertheless, if we evaluate the system today with the criterion of equality, we can say for sure that after 12 years of Georgian Dream rule, the system is one of the most unfair and unequal. This is reflected both in student evaluations and other indicators.

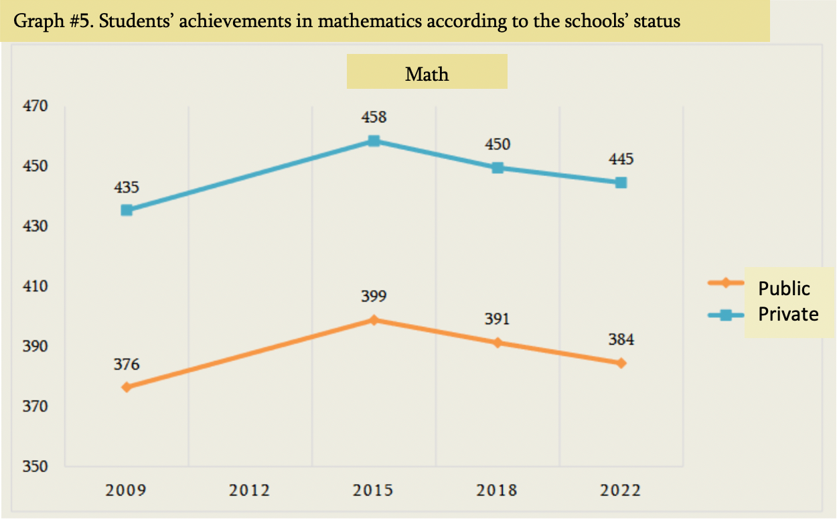

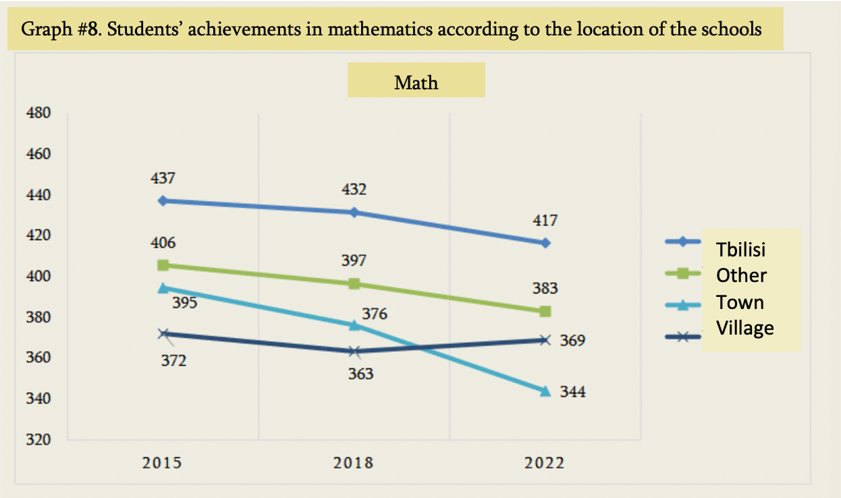

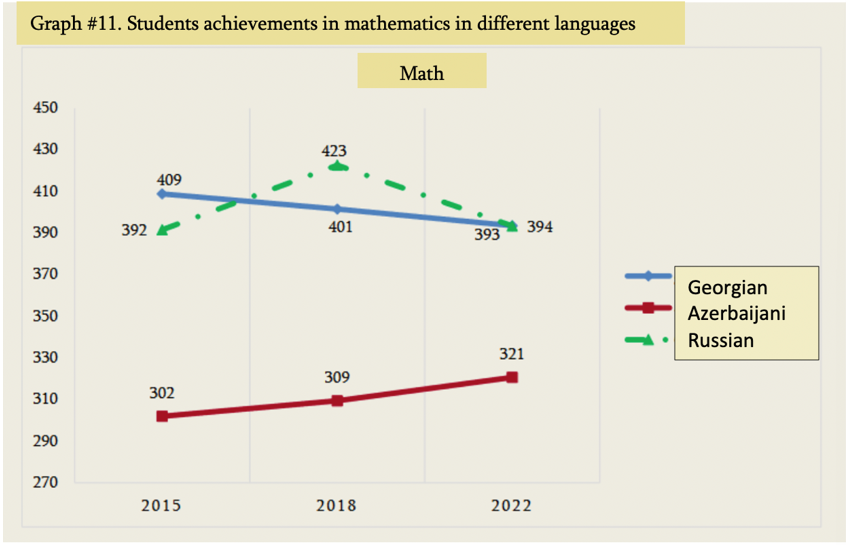

In terms of student evaluation, there are significant differences depending on the type of school (private/public), location (Tbilisi/other cities/township/village) and language of study (Georgian/Russian/Azerbaijani). Specifically, private school students achieve statistically higher results in all three assessment areas (math, reading, science) than public school students. Interestingly, if we look at the results of students of the same socio-economic status in both private and public schools, then there is virtually no difference between them. Therefore, we can say that this difference is mostly caused by socio-economic status and not by the type of school. Similarly, students living in Tbilisi show higher results than those in other cities, towns or villages, and Georgian-speaking students show higher results than non-Georgian-speaking students. This trend is manifested in both international and national assessments.

It is interesting that after 2012 nothing has actually changed in terms of the reform of national exams, which, despite high reliability, is one of the sources of inequality (Chakseliani, et. al, 2020). Under the current centralized examinations, due to the competition with city school students, rural and low socio-economic status students have much less chance of both getting into university and getting funding. This is caused by many factors, for example, high cost of living or the cost of preparing for exams, but the sad thing is that the system promotes and perpetuates such inequality.

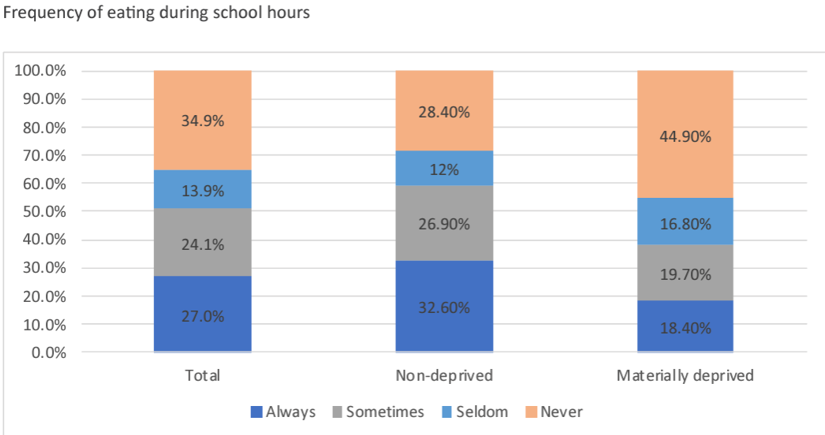

It is obvious that inequality is manifested in other indicators as well, for example, in terms of school meals. According to the United Nations Children's Fund, only 27% of students are fed daily during school hours. 35% are never fed, and among children with material and social deprivation, this number is even higher and reaches 45%.

Finally, the clearest illustration of inequality was apparent during the COVID pandemic, when households had to compensate for the ineffective response of the state in material form (for example, they had to purchase Internet or educational technologies, additional funds for tutors, etc.). Families with low socio-economic status could not afford the mentioned costs, thus fully or partially limited access to online learning. For example, the gap between urban and rural students' access to the internet was 20%. Only 52% of students from poor families used the internet, compared to 94% in urban areas. In this period, the involvement of students with special educational needs and ethnic minorities in the educational process was particularly problematic.

Stable instability

In the article, which turned out to be a bit chaotic, I tried to present the education system in terms of various factors, such as education goals and inequality. Of course, we have other factors as well. For example, in the 2022 report of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) about Georgia, we read, "Georgia is among the countries participating in PISA 2022, which showed stability and the results did not change statistically significantly compared to 2018." This opinion was conveyed even better by the Deputy Minister of Education, when he said that there is no improvement, but there is no deterioration either. Indeed, stability is one of the important characteristics of the education system. Ministers of education change frequently (since 2012, the minister has already changed seven times). Additionally, the reforms, whose names only remain in memory, are constantly changing. Accordingly, if we look at the system as a patient, we can say that 'the situation is steadily grave.' To improve the system, it is important to change the principles of management and restore its social function.

გამოყენებული ლიტერატურა:

გაეროს ბავშვთა ფონდი (UNICEF). (2023). ბავშვთა კეთილდღეობა საქართველოში 2023.

პაპიაშვილი და ბეჟანიძე. (2022). უმაღლესი განათლება და სოციალური სამართლიანობა. სტუდენტთა სოციალური საჭიროებების კვლევა.

ქადაგიძე. (2021). COVI 19-ის გავლენა სასკოლო განათლების სისტემაზე: პანდემიით გამოწვეული სასწავლო დანაკარგების შეფასება.

ჩახაია, ლ. (2019). სკოლის გამოსაშვები და ერთიანი ეროვნული გამოცდები საქართველოში.

ჭანტურია, ქადაგიძე და მელიქაძე. (2020). სასკოლო განათლების ისტორია: 1990-2020.

Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher's soul and the terrors of performativity, Journal of Education Policy, 18:2, 215–228, DOI: 10.1080/0268093022000043065

Chankseliani, M. (2014). Georgia: Marketization and Education Post-1991. Education in Eastern Europe and Eurasia, 277–302. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472593474.ch-014

Chankseliani, Maia; Gorgodze, Sophia; Janashia, Simon; Kurakbayev, Kairat (2020). Rural disadvantage in the context of centralised university admissions: a multiple case study of Georgia and Kazakhstan. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, (), 1–19. doi:10.1080/03057925.2020.1761294

Gert Biesta (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: on the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. , 21(1), 33–46. doi:10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9

Levin, B. (1998). An epidemic of education policy: what can we learn for each other? Comparative Education, 34(2), 131-142.

Lyotard, J.-F. (1984) The Postmodern Condition: a report on knowledge, vol. 10 (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

Noddings, N. (1995). Philosophy of Education. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB06490876

Tabatadze, Shalva; Gorgadze, Natia (2017). School voucher funding system of post-Soviet Georgia: From lack of funding to lack of deliverables. Journal of School Choice, (), 1–32. doi:10.1080/15582159.2017.1408000

[1] The fact that such a perception was formed and/or strengthened among a certain group of teachers, might be attributed to the work that we do through the education coalition. More specifically, in 2020-2021, we ran a "campaign to depoliticize schools," the goal of which was to promote school autonomy and reduce harmful partisan pressure. This is what was meant by the term "depoliticization", but it reminded the Georgian Dream of its programmatic promises and was misinterpreted by them. Finally, again as a result of discussions with colleagues and teachers, the name of the campaign was changed to "Teachers for Democracy".

The website accessibility instruction